"We Are Working To Live"

Tensions between Yale and the service industry that caters to the needs of the university's students have been high for decades—with no sign of letting up

This week, as students from around the country and around the world make their way to New Haven, Connecticut to attend Yale University, members of the city’s service industry community are bracing for another semester of mistreatment and elitist abuse.

New Haven is torn between the entitled elites that attend Yale and the working class that serves them. The rich kids that attend the Ivy League campus in downtown treat those they see as the help with disdain and disrespect.

Dan, a service worker in the city, told me that there’s a “constant feel of being dehumanized and felt less than with that school dominating the town” that manifests itself in the way students treat staff around the area.

“Yale dominates the city… it’s responsible for near constant gentrification and does nothing for the town,” Dan said. “I think all that trickles down to the general mood of being in the city as a non-Yalie.”

Your support makes these stories possible. For today through the end of September, take 20% a one-year subscription by clicking the link.

The Walled City

“There's been an increasing amount of animosity” in recent years between Yalies and New Haven residents, Chris, a former worker at the school’s bookstore, told me.

One of the nation’s most elite universities, Yale boasts a billion dollar endowment and counts three U.S. presidents as undergrad alumni and two as Law School alumni. The school, founded in 1701, has been a part of New Haven life for centuries.

The university owns $3.5 billion in tax exempt property in the city, leading to what amounts to a $157 million tax break, “even after accounting for their voluntary payments and the State College and Hospital PILOT payment that New Haven receives,” according to the watchdog website Yale Respect New Haven.

In response to reporting about its tax payments in January by NBC Connecticut, Yale defended itself on the merits of the revenue it brings into the city and its voluntary payments.

"Yale spends over $700 million annually directly on New Haven,” the university said in a statement. “This includes compensation to New Haven residents who work at the university and many programs and initiatives that we support throughout the city. Yale University’s $13 million voluntary payment in FY21 to the City of New Haven was the highest from a university to a host city anywhere in the United States and Yale continues to be among the top three real estate taxpayers in New Haven due to its Community Investment Program."

The Ivy League school, while ensconced in the New Haven downtown, is removed from its surroundings. The difference is noticeable as you drive into the campus area—a more modest urban area gives way to upscale shopping and cared for, manicured streets.

Yale has what amounts to its own police force and maintains a sort-of “walled city” within New Haven’s downtown, complete with high end retailers and restaurants. For many residents, the contrast with the rest of the city is indicative of the inequality that persists in the Yale-New Haven relationship.

“Entitled little shits”

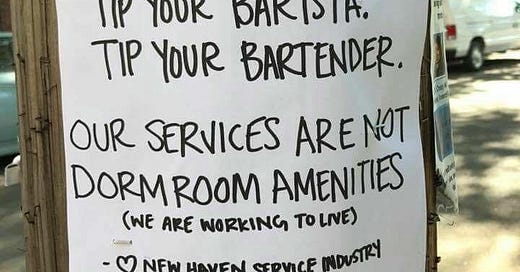

Students at Yale are hardly the only coeds in the country to treat local service workers with disrespect and tip them poorly. But the combination of mistreatment, poor tipping, and the elite nature of a large number of the school’s students leaves a bad taste in the mouths of many New Haven service workers.

“They will sign their checks and walk away so my coworker and I will literally call out their names to get their attention and then will point out where the tip goes,” Isabelle, a bartender in the city, told me. “Most times it leads to an argument about how they don’t need to tip us.”

Rick, a longtime New Haven resident, said that he’s seen both respectful and disrespectful students come through the school. Yale is not a monolith.

“As a waiter for nine years here I dealt with a lot of entitled little shits, but also a number of genuinely nice kids,” Rick said. “The undergrads are generally not regarded well by the waiters and bar staff I know but some of them get it.”

But the damage done to the community is from the sneering attitude toward service workers that manifests as dismissiveness, said George, a bartender in the city.

“The undergrads were shit tippers, but I’m willing to chalk that up to just being young and dumb,” George told me. “The real problem is their general sort of attitude that service workers were ‘the help.’ I’d sometimes get the impression that regular New Haveners were just a nuisance for them. Like flies buzzing around their heads or whatever. Just a lack of human courtesy.”

“They get trained to be that way”

Rick and other people I talked hastened to note that not all Yale students are like that. Many are on scholarship and receive financial aid, aren’t legacies, and have had to work hard to get there. But about half represent the elite backgrounds commonly associated with the school, with the $81,575 just for books, tuition, and housing—to say nothing of the other expenses of going to an elite school—paid for out of pocket.

“Notably about half of Yale undergrads don't need loans or financial aid,” Rick told me. “Not categorical but definitely a general class divide between the kids whose parents had $330K lying around and those that didn't.”

The elitist attitude of students toward the rest of the city is baked in, Rick told me, from the beginning of their time at the university. Yalies are taught to view their neighbors as threats.

“A few years ago I saw the freshmen doing orientation in August with their handler, and he was literally saying, ‘Don’t cross that street, over there they will rob you and kill you. Don't pay for your latte with a hundred—they won’t give you the change,’” Rick told me. “I mean, this town got a little rough circa 1980-2005 or so but come on. When I stopped laughing I realized that they get trained to be that way.”

If you liked this story, please consider a subscription.

Rick has his dates a little wrong, things were rough 1975-1990. By the time I left in 1987 the upscale places were already moving in. But he's right about the entitled little shits, my friends and I avoided them like the plague. They were toxic to each other, too - do you have to be a garbage person to get rich, or does being rich make you a garbage person?