Uncritical Race Theory

Conservatives complain about teaching students facts about history—but most school learning materials actually take the ahistorical approach they prefer

There’s something off about learning materials provided by Studies Weekly Dan Arel’s child uses for school.

“I have been helping my son with his social studies all year and noticing that this publication uses a lot of outdated language when discussing Indigenous people and early American colonies,” Arel, a San Diego-based writer and labor communications professional, told me.

Last week was worse than usual. The materials included a section telling students to “Learn about Jamestown’s African residents, who arrived beginning in 1619.” It’s a strange way to refer to victims of chattel slavery, which had its beginning in British North America in that very colony.

“As a country we’re still afraid to talk honestly about this county’s past and we whitewash the history,” Arel said.

Arel sent a complaint to the San Diego Unified School District. He is waiting to hear back.

The content of the Studies Weekly materials is indicative of what’s being actually taught in US classrooms about our history—a sanitized, ahistorical remembering of the past at odds with reality. And that runs counter to the current, and growing, right-wing panic over the possibility students might learn some facts.

Your support makes these stories possible. Subscribe today.

A history of bias

Studies Weekly’s outdated language and questionable materials have been the subject of controversy in recent years. The Utah-based company has raised eyebrows over insensitivity and bias.

As Education Week reported, a questionable Studies Weekly section on slavery was the subject of controversy nearly four years ago:

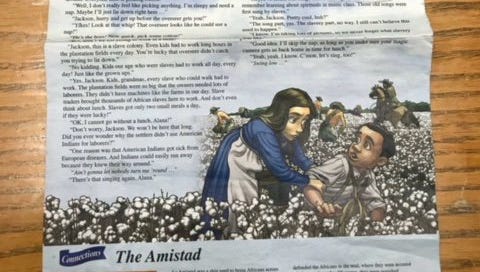

In February 2018, the company came under fire for an article included in a 5th grade publication. The short fiction, titled “Cotton-Pickin’ Singing,” told the story of a white girl, Alana, and a black boy, Jackson, who were magically transported back to Georgia in the 1700s. Alana explains the history of slavery to the boy in a passage that includes several historical inaccuracies—including the false statement that white colonists didn’t also enslave Native Americans. As she talks, Alana directs Jackson to pick cotton to appease the overseer. Parents in the Monroe County, Ind., school district voiced concerns about the lesson, and, as a result, the school board ended its contract with the company.

In 2018, an internal review of the company’s materials obtained by Education Week “found more than 400 examples of racial or ethnic bias, historical inaccuracies, age-inappropriate content, and other errors.”

That report figured into North Carolina’s Guilford County School District’s decision this summer to review the company’s materials for bias. In response to the review, Studies Weekly Chief Marketing and Support Officer Melody Anderson told the News & Record, based in the Guilford County city of Greensboro, that all 400 examples of bias had been “corrected.”

“We conducted that internal review to identify articles for revision because we knew that the way history had once been taught was no longer acceptable,” Anderson said.

But the learning materials Arel’s son was given indicate that Studies Weekly’s bias hasn’t gone away.

“Each week I read over and help correct him in how he speaks and what he learns,” Arel said. “It’s a very whitewashed publication.”

Whitewashed history is just what conservative parents and right-wing activists want.

“The perfect villain”

Despite the fact that nothing of the sort is actually going on, far right figures have been raising the alarm all year that Critical Race Theory is being taught in schools. The panic began with activist Christopher Rufo, who started working to get the term into the public consciousness while covering Black Lives Matter protests in 2020.

Rufo detailed the goals of promoting CRT in an email to New Yorker writer Benjamin Wallace-Wells. Explaining that the term “political correctness” has lost its bite, Rufo said that “the other frames are wrong, too: ‘cancel culture’ is a vacuous term and doesn’t translate into a political program; ‘woke’ is a good epithet, but it’s too broad, too terminal, too easily brushed aside. ‘Critical race theory’ is the perfect villain.”

His “villain” found a ready and eager audience. Matt Taibbi called CRT “both more interesting and more frightening, than the narrow race theory that has Republican politicians in maximum wig-out mode.” Writer Andrew Sullivan, whose personal history of bigotry is too long to detail here, jumped on board, warning his audience of CRT’s power to brainwash children.

“Ibram X. Kendi even has an AntiRacist Baby Picture Book so you can indoctrinate your child into the evil of whiteness as soon as she or he can gurgle,” Sullivan wrote in June. “It’s a little hard to argue that CRT is not interested in indoctrinating kids when its chief proponent in the US has a kiddy book on the market.”

Of course, CRT is not being taught in K-12 schools. The highly technical, narrowly-focused teaching technique is used in legal education and by activists. Proponents of the threat posed by CRT seldom if ever define it or what it is. Tucker Carlson has “never figured out what critical race theory is, to be totally honest, after a year of talking about it.”

A more honest conversation

Today, CRT has become something of a catch-all phrase that means teaching children basic facts about US history.

“Critical race theory began to stand for any teachings that challenged the narrative that white America had crafted about the country, and that unveiled any truths that it had tried to hide or erase,” Charles Blow wrote in June.

As you’d expect, that’s made a number of people very angry.

Right-wing politicians are taking notice. The outrage machine’s promotion of the term has led to conservative parents around the country making the fight against it a top priority.

But the reality is that even the recent move toward introducing a more well-rounded understanding of US history—the role of race in the brutal expropriation of Native American land, slavery, and the systemic challenges for people of color in the country—is a drop in the bucket compared to the overwhelming advantage held by the right in American schools.

To Arel, the bias in Studies Weekly materials is indicative of a bigger problem.

“It highlights the need to reevaluate and rewrite outdated school text and have a more honest conversation with students about this country and its roots in white supremacy,” he said.

If you liked this story, please consider a paid subscription.