The White Backlash to the Civil Rights Movement

The United States of America was deeply affected by the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. Upending centuries of white privilege and decades of official and unofficial racial segregation, this movement fundamentally reshaped the country’s cultural, social, and political landscape. Change did not come without cost, unfortunately, and one of those costs was white backlash because of the erosion of the privilege they had come to view as their right. The historical scholarship of the past 22 years has shown that this backlash took many different forms, but one thread can be seen throughout: white Americans’ resistance to a changing racial reality seldom was immediate, often was veiled in non-racialized language, and always had justifications that had little to do with race. In general, white backlash stemmed from resistance to an integrative racial order that attempted, at least in spirit, to dissipate white privilege and create a pluralistic and color-blind society.

Over the past generation, scholars have investigated white backlash against the civil rights movement. To study the evolution of the scholarship on the topic of white backlash against the civil rights movement, and its effects on the conservative resurgence at the end of the 1970s, eight books will be reviewed here: Lisa McGirr’s Suburban Warriors: The Origins of the American Right, Mark Brilliant’s The Color of America Has Changed: How Racial Diversity Shaped Civil Rights Reform in California, 1941–1978, Jefferson Cowie’s Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class, Kevin Kruse’s White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism, Matthew Lassiter’s The Silent Majority: Suburban Politics in the Sunbelt South, Ronald Formisano’s Boston Against Busing: Race, Class, and Ethnicity in the 1960s and 1970s, Thomas Sugrue’s The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit, and Walter Greason’s Suburban Erasure: How the Suburbs Ended the Civil Rights Movement in New Jersey. Each of the eight books under review deal with the civil rights movement in specific areas of the United States, and each shows, to greater and lesser degrees, the white reaction to the movement’s successes. All the eight books are relatively recent. With the exception of Formisano’s and Sugrue’s books, they were all written within the past twelve years, and even the former’s studies appeared in the past 22 years. By considering these books in the order listed above, the reader can see the origins of the right wing movement both in California and nationally, the reactionary basis for the growth of the right wing in California and the South, and the fact that the white backlash was not localized within those regions, but was, rather, a national trend. The scholarship of white backlash, as these studies make clear, shows the disparate reasons for the backlash, among them the white working class’s economic and social insecurity, their property value concerns, and worries about social mobility and feelings of middle class pride, that refute the contention that white backlash was solely a racial reaction to a new racialized world created by the civil rights movement.

Before launching into the review of the literature, it is important for the purpose of this essay to define two terms. “White backlash” means the legal and social fight against the victories of the civil rights movement. This backlash took varied forms, at some times electoral victories for the right wing, at other times it came in the form of legislation that attempted to push back against laws such as Proposition 14 in California, which struck down the Rumford Act’s integrated housing in California until it too was overturned by the courts. “White privilege” means the elevated social status of whites. In the South, Jim Crow laws codified discrimination against blacks and segregation, but in other regions, discrimination prevailed because of the lack of laws preventing it, such as in Michigan, where only a non-discrimination law in 1955 prevented discriminatory hiring practices.

Lisa McGirr’s 2001 book, Suburban Warriors, addresses the white conservative movement’s deep roots in Orange County, California. She argues that, far from being the singular result of a backlash to the civil rights movement, conservatism was always alive and well in white America. The power of the conservative movement was not always apparent because the New Deal and victory in World War II had made liberalism the hegemonic political philosophy in America; however, in places like Orange County, a bastion of professionals who mainly worked in the military industry, a conservative political worldview was dominant. The conservative reawakening that was taking place in states like California was dismissed as unimportant by liberals and the political class, and not indicative of a wider trend nationally. As McGirr shows, this perception of the right wing was woefully inaccurate. She finds that the right’s mobilization from the 1950s to 1960s constituted a large and strong movement that was overshadowed by the left wing’s more colorful actions and victories in the same period.

Similarly, Mark Brilliant finds in The Color of America Has Changed that the white conservative movement reacted to minority gains by coalescing around Ronald Reagan’s 1966 campaign for governor, and that this was a result of the nascent conservative movement in the state. Brilliant’s 2010 book adds to the work McGirr began in 2001, by addressing the electoral, political consequences of the rise of the conservative movement in California after the victories of disparate minority groups in the state. Color of America in conjunction with Suburban Warriors adds to our understanding of the origins of white backlash in California and the nation, and helps to explain the political motivations and history of the white conservative movement.

Undoubtedly, the minority victories in California described by Brilliant contributed to the growth of the conservative movement as the white backlash against the erosion of their privilege grew. This backlash expressed itself in the anger against the striking down Proposition 14’s reintroduction of discrimination in housing, anger which helped to elect Ronald Reagan as governor in 1966. Brilliant explains that Proposition 14, which resisted racial integration in housing and communities, was an attempt by whites to reassert their privilege. It was not necessarily racially motivated: the margin of victory for Proposition 14, at almost 2 to 1, was roughly the same as the margin of victory for Johnson over Goldwater. Integration of white communities drove property values down, and, for many working and middle class whites, the right to private property was an important one. Despite the fact that Proposition 14 ultimately failed, it shows the resistance to change by whites that would later translate into electoral success for the conservative movement’s party, the Republicans.

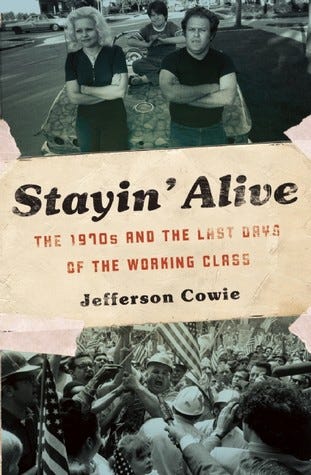

In Jefferson Cowie’s 2010 book, Stayin’ Alive, these dynamics of shifting political allegiance also come into play, as Cowie studies the hardhat working man’s conversion from liberal icon in the beginning of the 1970s to conservative icon by the end of the decade. A changing world in which the working white man felt powerless drove the seemingly contradictory statements of Dewey Burton, who, in the introduction, is quoted as, chronologically, first a supporter of George Wallace, then of George McGovern, then of Ronald Reagan. This swinging of the pendulum from right to left and back again is explained by Cowie as motivated by a feeling of impotence that stemmed from Burton’s and other white working class men’s sense of a rapidly changing world and uncaring elites who both helped minorities at the expense of whites and maintained their power through the destruction of unions and worker’s rights.

Jefferson Cowie’s scholarship on the white backlash of the seventies has parallels with an earlier book, Kevin Kruse’s 2005 study of Atlantan suburban culture, White Flight, particularly as both studies address the political struggle of both preserving white privilege. Where Cowie concentrates on the decade of the seventies in general, and is not concerned with specific regions, Kruse concentrates on the suburbs of Atlanta and their changing demographics in the wake of the civil rights movement. Both authors deal with white backlash and the double response that often occurred of both fighting against the civil rights gains and not wanting to appear to oppose progress. For Cowie, the seventies are the decade in which the white working class was finally overwhelmed by the massive social changes of the civil rights movement and decisively turned to a conservative political stance, while keeping its language and reasoning color blind. For Kruse, on the other hand, the Atlantan business community’s need to attract investment and consumers led to a branding of the city as “Too Busy to Hate,” despite the fact that the city’s whites were too busy moving out to the suburbs to be around people of color whom they could hate. White Flight analyzes the civil rights struggles in Atlanta and the white flight from the city. As with McGirr’s findings in Orange County, Kruse’s study sees the white backlash against the civil rights movement as rooted in the pre-existing conservative ideology in the suburbs of Atlanta. By the mid-1950s, those white communities which successfully resisted integration were uniform in their community’s resistance. The uniformity of this response was intensified by their isolation within their all-white suburbs, which, as in Orange County, bred a strain of conservatism that would lead both regions to vote overwhelmingly for Barry Goldwater.

White Flight’s analysis of the Atlantan white backlash and the flight to the suburbs is expanded upon by Matthew Lassiter’s Silent Majority. In White Flight, Kevin Kruse introduces the reader to the Atlantan civil rights demonstrations and their successes and resistance. By showing how the liberal victories of the 1950s and 1960s led to a white exodus from the city and into the suburbs, his work sets the stage for Lassiter’s in depth study of the busing fights in Atlanta. Lassiter studies the anger and frustration felt by suburban white southerners at the forced integration that was destroying their postwar attainment of middle class status. Lassiter argues that the resistance to integration in Atlanta and Charlotte led directly to the idea of the silent majority, the idea of the majority of the country possesses particularly conservative ideals and is uncomfortable with the social changes of the civil rights movement. Lassiter, who published in 2006, one year after Kruse, acknowledges the fact that their studies overlap. In fact, in the acknowledgements of both books, Lassiter and Kruse thank each other for their respective input. Thus, the reader can assume the conclusions each reaches are related and build upon the work of the other. White Flight and Silent Majority are different books that have different aims, but have more than a few converging topics and conclusions. Aside from the obvious similarities in their subject matter, both Lassiter and Kruse point out that Atlanta’s self-perception of an enlightened and modern city was belied by its actual resistance to change and the official and unofficial segregation of their black and white communities. Both books address the feelings of middle class pride and its challenge and devaluation by integration. Both books also address and contest the mythology that the Atlantan business community solved the school desegregation conflict. Rather, they argue that this success was more a result of fortunate timing than anything else, and the credit taken afterwards was simply a case of taking advantage of a fortuitous situation.

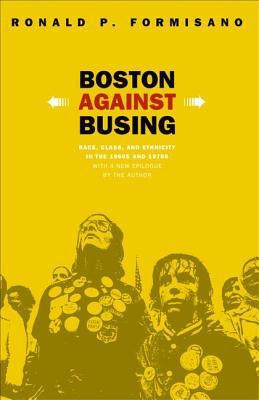

Silent Majority tells a story of resistance to integration in the south, but resistance occurred in the north as well, for many of the same reasons. Ronald Formisano’s 1991 work Boston Against Busing describes the violent and racist attacks on busing by white Bostonians in the 1970s, and shows that white backlash was more complex than simply a race-based reaction to integration. Boston’s and Charlotte’s experiences in the antibusing movement were similar but different. Both cities underwent the forced integration of their schools and resisted. Both cities were integrating school districts in neighborhoods which were white, but middle class. Both cities formed organizations to pool their resistance efforts. A recurring theme in all the books discussed in this paper is the class system which protected the white elite from the measures they imposed on lower class whites to achieve racial integration. In Boston and Charlotte, as well as in Atlanta, this class divide was noticeable. Many whites in all three cities felt that their work to climb the social ladder was being destroyed almost as soon as they had achieved middle class status. Thus, the anger provoked by busing and integration in these three cities can be seen as much a product of class rage as of racial hatred, again referencing Jefferson Cowie’s introduction which cites the odd voting pattern of Dewey Burton. Burton truly wanted someone in office who would stand up to the elites, whom he, as well as many white members of the working class, saw as both engaging in social engineering and not having to deal with the consequences.

Boston was hardly the only northern city with racial problems, however. Detroit was a city with de facto segregation, as Thomas Sugrue notes in his 1996 book, The Origins of the Urban Crisis. Urban Crisis shows that in Detroit, much as Kruse shows was the case in Atlanta in White Flight, the white population segregated itself from the black population by fleeing to the suburbs. The black population of Detroit grew in the early twentieth century, and the resulting integration of the city was mistrusted, to say the least, by its white autoworkers. Sugrue’s research into the integration of blacks into white communities and workplaces in Detroit shows that despite the city’s northern geography, and the lack of actual Jim Crow laws to enforce segregation and inequality, the city’s racial problems were very similar to those of cities in the south. Detroit whites, like their southern counterparts, feared that the integration of blacks into their neighborhoods would drive down property values. In Detroit, employment discrimination based on race was widespread and common even after the passage of equal rights legislation in 1955. Housing discrimination marginalized poor blacks who needed assistance and neighborhood integration. Integration was resisted by whites with the usual language of “rights.” By choosing to have his discussion focus on the city of Detroit, Sugrue explains the roots and causes of white backlash, in a way that also displays for the reader the consequences of class divisions. Sugrue’s work is extraordinarily influential in the field of U.S. history; his name appears in two of the acknowledgements in the books discussed in this essay as a helpful source and conversationalist. Thus, Urban Crisis stands as an important piece of the scholarship in the study of white backlash, although it comes at least a decade before all but one of the books in this essay. Not only can one infer that Sugrue’s research has had an effect on the other scholars, but their acknowledgements show that his work and knowledge are an important part of the work on the subject.

In his 2013 study of rural New Jersey blacks, Suburban Erasure, Walter Greason discusses both pre- and post civil rights movement New Jersey, lending a broader perspective to the roots and causes of later white backlash. Greason argues that the white backlash against the civil rights movement was as much about the failure of America to create a just and equitable society in the first half of the twentieth century as it was a backlash against the victories of the movement in the 1950s and 1960s. The migration northward by blacks in response to violence in the south, and their encroachment into white towns and neighborhoods in New Jersey led to a natural segregation of those areas as whites moved away. Despite the fact that society was heavily invested in New Jersey in maintaining the racial hierarchy that kept white privilege in effect, black activists in the towns where blacks settled managed to win, to varying degrees, battles for basic municipal rights. Predictably, the issue of privilege became a motivator for whites, who did not appreciate having to provide services for their fellow citizens who happened to be black. By self-segregating, whites created boundaries and distance, as well as maintaining differences in property values, between the races. Greason references ideas of racial purity as defining the segregationist cause in the early years of the United States, and argues that these attitudes and the actions of racial separation became tradition over many years (Greason says there is evidence that traditions of segregation and racial separatism began as far back as the late seventeenth century). In fact, for all the technical successes of local activists in New Jersey and the civil rights movement as a whole in this country, segregation continued, and continues, to this day.

The scholarship in the field of white backlash against the civil rights movement in the past twenty-two years has offered great insight on the subject. From Formisano’s work on the Boston busing fights in 1991, which definitively tells the story of a stain on the enlightened reputation of the northeastern city, to Greason’s 2013 work on rural New Jersey blacks and their struggles, and the white power structure’s self-segregation in reaction to these varying degrees of victory, the past two decades or so has been a revealing time for the historiography. Formisano and Sugrue’s works were both published in the 1990s, and their findings on the topic of white backlash rely heavily on a class based perspective. For Formisano, the Boston antibusing movement was as motivated by the upward mobility and feelings of middle class pride that the whites of South Boston had as it was on racial divisions. Similarly, in Detroit, Thomas Sugrue shows that Detroit whites’ feelings of pride in having achieved middle-class status had a great deal to do with their flight to the suburbs. Both studies find that white backlash owed a great deal to feelings of anti-elitism and a desire to hold onto one’s sense of class.

Lisa McGirr, Kevin Kruse and Matthew Lassiter wrote their books in the early 2000s, and the availability of sources, as well as general interest in the topic, had increased by the time they began their work. McGirr’s 2001 work upends the idea that white backlash was a purely reactionary movement, and instead examines the deep roots of conservatism in white America. White backlash was simply the vehicle by which this already large movement could deliver its message to the broader public. Kruse, too, finds that blaming the backlash on reactive forces is too simple an explanation for the rise of the right. His 2005 examination of Atlanta describes how the white population of Atlanta was able to mask its racist and segregationist attitudes by removing itself from the city and moving to the suburbs, where its conservatism had a perfect environment in which to grow. Lassiter also comes to this conclusion in 2006, although he concentrates more on the idea of the silent majority- that members of the white conservative movement, seeing their world changing so quickly, believed that their perspective on the world and their rights was more universal than not and their movement gained a moral justification from this notion of the silent majority.

Finally, the work in the later years of the decade by Brilliant, Cowie, and Greason integrates the earlier scholarship and shows the direction of study in the field today. Brilliant takes on the entirety of Californian minority politics, and in doing so, lends a newer, and clearer, look at white backlash in the state that elected Ronald Reagan. The individual reductions in white privilege in California that various minority groups achieved were in total too much of a challenge to the white hegemony of the time, leading to a full rejection of government interventions employing the language of “rights.” Cowie explains that the evolution of the hard hat working man from liberal to conservative icon in the decade of the seventies was rooted in the white working class’s feelings of helplessness as their white privilege was taken from them at the same time as their careers were wrecked by a changing economy. The seventies ended with the appropriation of the language of populism by Reagan, who disguised the truth about his conservative policies by relying on anti-elitist and reassuringly authoritarian rhetoric. And Greason explains the process by which, even in the liberal Northeast, whites maintained their privilege by segregating themselves from the black interlopers (as they were seen by whites) who moved into their towns. New Jersey is hardly alone in this, but Greason’s concentration on the rural townspeople’s experience of blacks, and the wider racial divisions that have existed for centuries, gives deeper understanding to the reasons for white backlash.

The scholarship presented in this essay on white backlash is strong, but there are certain areas in which all these studies display deficiencies. Chief among these is the absence of the female perspective in the books. White families, workers, and men are consistently cited and presented, but the experience of women in the white backlash against the civil rights movement is woefully underrepresented. Also, with the exception of Mark Brilliant’s study, all the works discussed focus wholly on the black/white conflict. The experiences of people of color other than blacks in America during the time period of the civil rights movement and the white backlash are also important and can help us to gain a clearer understanding of the time period. Finally, although the political and business elites’ interests and their manipulations of white anger to further their ends are mentioned quite frequently in the books, the field of study would benefit greatly from an analysis focused directly on the experiences of these elites. Though the elites were involved in the legislation and forceful process of integration, the consequences of this integration hardly, if ever, reached their communities. It would be interesting and important for the historiography if the elites’ participation in and view of white backlash and the civil rights movement were documented.

The white backlash against the civil rights movement and against the victories of liberalism ushered in the age of conservatism that we still live in today. The scholarship of the authors whose works are discussed in this essay has added to our understanding of why conservatism became such a strong and vibrant political force in the later years of the twentieth century and the early years of the twenty-first. From antibusing movements to self-segregation, class concerns to racism, the origins of, and reasons for, white backlash are varied. The historiographical works discussed here all work together to explain how these varied reasons all coalesce into a whole. White backlash was a reaction to the civil rights movement, but the foundations of conservatism were already in place. The conservative movement used white backlash as the vehicle by which their “silent majority” came into political power. The class insecurity of the white middle class led to a feeling of anti-elitism that further exacerbated their backlash to what they saw as social engineering imposed by those who governed them. Despite some deficiencies noted above, the scholarship of these eight authors has helped to invigorate the study of white backlash.