And that means leaving Bernie behind.

Over 160 years ago, an idealistic politician from western New England became a standard bearer for a new political party. If that sounds familiar, it should.

Progressives have proposed taking the momentum of the protest movement opposed to the Trump presidency and push it towards a new, progressive party headed by Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders.

There’s one problem. Sanders confirmed to Meet the Press in February that he has no intention of leaving the Democrats. But supporters of the political revolution Sanders called for on the campaign trail should not be disheartened — these things take time.

The Republican Party’s experiences in the Massachusetts gubernatorial election of 1855— and that election’s aftermath— provide the road map to future electoral success. And part of the plan necessitates leaving Bernie behind.

The Republican Party formed in Wisconsin in 1854. Disaffected Whigs and “Free Soil” Democrats, concerned over the expansion of slavery in the west, rejected the Whig Party’s impotent opposition to the pro-slavery Democrats. The writing was on the wall — only a new party would be sufficient to stop the expansion of slavery. The binary of the national two party system was unworkable.

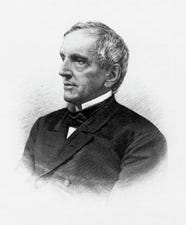

In Massachusetts, the Republican Party’s 1855 candidate for governor in Massachusetts — and one of the national party’s first candidates for statewide office in the country — was Julius Rockwell of Pittsfield. The former Whig had served first as a Congressman in the 1840s, and then briefly as a Senator in 1854.

Rockwell was known for his devotion to abolitionism, a cause that he believed was a matter of right and wrong, good and evil. Rockwell’s independence won him respect in Washington. He counted Charles Sumner as a friend. A young Congressman from Illinois named Abraham Lincoln sought Rockwell’s advice when he came to the Capitol in 1847.

As the Republicans’ gubernatorial candidate, Rockwell faced the Know-Nothing candidate for Governor of Massachusetts, Henry Gardner, a candidate from a party that had its roots in anti-immigrant sentiment.

The Know-Nothings did quite well in Massachusetts in the mid-1850s. Their message was clear: the economic woes of the nation could be traced to the influx of migrant labor to the country.

David Davis, Rockwell’s brother-in-law and the executor of Lincoln’s estate, told Rockwell in March of 1855 that the Know Nothing success in Massachusetts “was past my comprehension.”

“It would not have seemed strange in one of the Western States,” Davis wrote Rockwell, “but that an entire people educated and enlightened as they are in Massachusetts should have done so, is passing strange. There certainly has been nothing like it in the history of politics.”

But Davis needn’t have worried. Rockwell lost to Gardner in the election, but his candidacy inspired a future generation. While historian Martin Duberman asserts that the result of the election “proved disappointing to the new party,” the vote totals paint a different picture. The Republicans came in at 27% of the statewide vote — an impressive total for a brand new party.

As for the Know Nothings, they watched their share of the vote plummet from 79% of the vote in 1854 to 38% in 1855. They were a flash in the pan and saw their xenophobia and paranoia evaporate as a political strategy. The party largely died out by 1860.

The twin experiences of founding the Republican Party of Massachusetts and fighting in the Rockwell campaign were formative in the careers of young politicians who would go on to greater political success in the future. Richard Henry Dana, Nathaniel Banks, Robert Carter, and Moses Kimball all credited the campaign as a formative moment for their political careers. By their own post-election correspondence with Rockwell, Rockwell’s failed candidacy inspired them and his resolve strengthened their own.

Rockwell tried to run again for governor in 1856 but was politely rebuffed. His time had passed. The Republicans realized that looking backward would not help the future. Their Massachusetts electoral loss in 1855 was only the beginning of a powerful political movement. And while Rockwell was a respected statesman the future of the party lay elsewhere.

Progressives should emulate the early Republicans. As the progressive movement pushes forward, it should do the same for Sanders that the Massachusetts Republicans did for Rockwell. Sanders’ work to inspire a new generation of politically active idealists in 2016 was invaluable.

Now it’s time for the movement to continue moving forward — without the candidate of the past.

Like my work? Please consider supporting me via my Patreon. $5 a month gets you interviews, reading lists, and more.