Selective Outrage: Trump and the Pershing Myth

In US politics, some bigotries are less offensive than others.

In US politics, some bigotries are less offensive than others.

When President Donald Trump repeated an extremist right wing talking point with its roots in racial hatred and xenophobia on Thursday, it wasn’t anything new. The president had used the slur before. And the events of the last week have shown that Trump is doubling and tripling down on his white nationalist rhetoric as he stiffens in the face of unprecedented criticism and pushback from members of his own party over his response to the violence from last weekend in Charlottesville, Va.

But while Trump’s insensitivity to the victims of white nationalist attacks and his moral equivalency between white supremacists and those who oppose them have garnered him a wave of condemnation, his remarks endorsing an Islamophobic fairy tale have not. Perhaps the reason is that there are no consequences for spreading lies, fear, and hate in America, even if you’re the president, as long as you pick the right target.

On Thursday evening in the Spanish city of Barcelona, a van was used to attack crowds on the popular Las Ramblas street. 13 people were killed and 80 were wounded. The driver is still at large and the investigation is ongoing, though the Islamic State terror group claimed responsibility for the attack on Thursday evening.

When Trump took to Twitter to address the attack, he began by sending the nation’s sympathies to the Spanish people and promising the support of the American people.

Less than an hour later, Trump tweeted out a discredited right wing myth that has its basis in a repugnant stereotype of Muslims and used language that stopped just short of promoting mass murder.

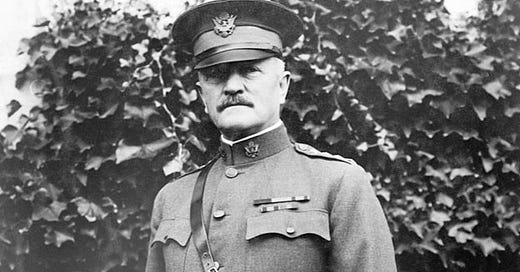

Trump was referring to the false story of how General John J. “Black Jack” Pershing defeated a 1911–1913 insurgency in the Philippines in the majority-Muslim Moro Province. According to the baseless version of Pershing’s counter-insurgency tactics, the general soaked bullets in pig’s blood and killed 49 insurgents with them before turning to the 50th and telling him to return home and tell the rest of his people what had happened. The truth is that Pershing was a more measured commander and took a pragmatic approach to the insurgency — the general’s record does not suggest that he would have taken such an action as it would have been extremely counter-productive.

The tweet was the latest in a series of extremist rhetorical statements from Trump, who has faced escalating criticism for his response to the violence of Aug. 12 in Charlottesville, Va. After a white nationalist rally in the city was disbanded, counter protesters marching down a city street were attacked by a car driven an alleged white supremacist named James Alex Fields, Jr., of Ohio. A woman named Heather Heyer was killed during the attack.

The president’s initial statement cast blame on both the white nationalist movement and those who were there to oppose it; a follow up on Monday clarified that the president condemned the white supremacist ideology. But on Tuesday, during an erratic and combative impromptu press conference at Trump Tower in Manhattan, Trump walked back his condemnation of white nationalists and instead doubled down on his initial statements condemning “both sides” of the Virginia protest.

Outrage followed the president’s remarks on the Charlottesville attack. He has suffered under a storm of increasing criticism — much of it from elders in his own party. It seems that for GOP leaders, taking the side of neo-Nazis and the Ku Klux Klan is a bridge too far. But Trump has faced almost no pushback at all for his comments on Pershing.

The story remains popular in hard right circles because it hits on a number of xenophobic talking points: that Muslims have a supernatural aversion to pork, that being tainted with pig’s blood will deny Muslims entry to paradise, and that the only way to deal with Muslims is through extreme violence because their lives are unimportant. The story is widely understood to be completely false and rooted in racism, yet it’s not the first time it’s come up in the past decade and a half.

The myth has persisted in American culture and been used to further anti-Muslim sentiment, especially since 9/11. In July 2005, the California National Guard came under fire for a recruitment poster in Sacramento showing bullets dipped in pig’s blood and asked if the Iraq War needed another Pershing. The poster was removed.

In 2011, the Silver Bullet Gun Oil company claimed that gun oil it had produced with 13 percent liquefied pig fat was used as gun lubricant during the raid that killed Osama Bin Laden. Members of the military, the company claimed, bought the oil — including the Navy SEALs that killed Bin Laden.

Silver Bullet weren’t the only company trying to make money off of the Pershing myth in the last decade. In 2013, Gawker’s Cord Jefferson reported on a company called Jihawg Ammo that sold bullets coated in a pork-based paint. The company — which no longer exists — referenced the Pershing myth and said that the bullets were the best line of “self-defense” against a growing Muslim threat.

Trump himself thrust the mythology into the mainstream on the campaign trail. During a rally on Feb. 19, 2016, in North Charleston, SC, the future president told the crowd that Pershing’s use of blood coated bullets was instrumental in stopping the insurgency: “Twenty-five years, there wasn’t a problem.” Trump’s comments inspired a group of white men in Texas to train with bullets dipped in pigs blood against the threat of a “Muslim uprising.”

What all these instances of the mythology show is that the story is used to call for violence toward Muslims. On Thursday, like in 2016, the president was calling for mass killings of Muslims to send a message.

It appears that the president won’t suffer any political fallout for calling for mass murder. Not one GOP leader thus far has come out against the president’s tweet and its underlying message. The racist undertones of the message are acceptable because the target is the Muslim community, a group that has been systematically marginalized and harassed at all levels of American society for the past 16 years.

In U.S. politics, there are some things you can say and some things you can’t. When it comes to promoting the cause of white supremacy in the face of murder allegedly inspired by that ideology, that’s saying the quiet part loud. You’re not supposed to do that. But when it comes to casting aspersions on an entire religion and implying that that religion’s adherents should be murdered until they do what you want, that’s acceptable — as long as they’re Muslim.

Subscribe to my Patreon for exclusive access to essays like this one and twice weekly readers.