Reform to Revolution: The Ideological and Political Evolution of James Connolly

This essay was first published at The Hampton Institute.

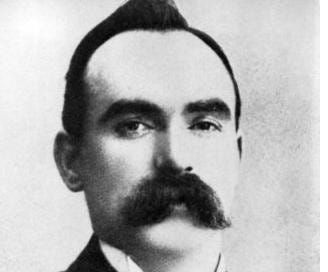

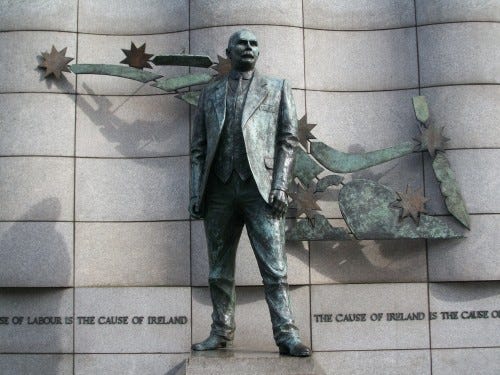

James Connolly is primarily remembered in Irish history as the Socialist revolutionary hero of the Rising of 1916, executed in Kilmainham Prison while strapped to a chair.

Connolly’s place in Irish history is far more important than that, however. He was a proud Socialist, the founder of both the Irish Socialist Republican Party and the Labour Party, and the writer of the influential pamphlets Labour in Irish History and The Reconquest of Ireland.

Connolly’s political pragmatism in forming the Labour Party was the culmination of idealistic defeats that began with the dissolution of the ISRP in 1904. He believed that in order to effectively challenge the hegemony of British imperial capitalism, he had to attempt to work within the capitalist political system to achieve his goals. The eventual challenge he posed to the system from within led to his own political repression at the hands of British imperialist forces. This repression, in turn, led Connolly to resort to violent rebellion in The Easter Rising of 1916.

In the two contexts in which they were written — for Labour in Irish History, the ISRP’s history and fate; for The Reconquest of Ireland, the reaction of capital to the growing successes of the Labour Party and Connolly’s rebellious response — Connolly’s pamphlets are understood better.

Here we will only deal with two distinct periods of Connolly’s political development: his involvement in the formation and the dissolution of the Irish Socialist Republican Party, and his role in the Rising of Easter 1916. Similarly, only the pamphlets Labour in Irish History and The Reconquest of Ireland will be discussed because they most closely align with the periods in question. This essay will tie together Labour and Connolly’s work with the ISRP. Though there was an intervening period of six years between the dissolution of the ISRP and Labour, Connolly’s political work strongly influenced his writing of the pamphlet. Reconquest and Connolly’s involvement in the revolutionary Irish Provisional Government are more closely and identifiably tied together, being contemporaneous and of the same aim.

The Irish Socialist Republican Party

Connolly arrived in Ireland from Scotland in 1896 after answering a job posting of the Dublin Socialist Society for a secretary of their fledgling organization. The Dublin Socialist Society wanted more prestige and a propaganda wing, and believed that in Connolly, they had found their man. He proved up to the task and, with six other members, formed the Irish Socialist Republican Party out of the Dublin Socialist Society within weeks of arriving in Ireland. The formation of the Party was an important step for both the socialist cause and Connolly, as it allowed for consolidation of resources and a centralization of the left wing of Ireland. The ISRP also gave a platform for those in Ireland whose opposition to the British Empire was rooted as much in an opposition to the capitalist system as it was to the subjugation of the Irish by the British.

The ISRP called itself a Socialist Republican Party because the aim of the party was two-fold. On the one hand, the republicanism came from a desire to break the yoke of the British and establish a free and democratic Ireland. Irish liberation was never far from the rhetoric of the ISRP. The ISRP spoke to the working class of Ireland and implored them to escape from the domination of the imperial capitalist British Empire.

On the other hand, the socialism in the party’s name came not only from the rhetoric but from the aim of the party to establish a Socialist republic. A free Ireland was not the sole aim of the ISRP. The Ireland that emerged from the domination of the British needed to be a socialist state to ensure the exploitation of the Irish poor would not continue under whatever new republic took hold.

Connolly’s involvement in the Party was extensive. He was a founding member and was the most outspoken member. His writings and speeches found their way not only into the homes of the literate Irish, but also across the ocean in America, where he would spend time between the dissolution of the ISRP and his return in 1910. As de facto leader of the ISRP, Connolly made friends and enemies alike with his, at times, acerbic personality.He was highly driven to expand the scope of Irish republican socialism from simply the province of the intellectual freedom fighters of Dublin and Belfast to a nationwide movement.

As chief agitator and propagandist, Connolly was front and center in the party’s public image. Connolly also took a role in financing the Party. As he put it, “the founders [of the ISRP] were poor, like the remainder of their class, and had arrayed against them all those things that are supposed to be essential to [political] success.” Therefore, financial stability was of paramount importance for an organization that was devoted to overthrowing the hegemonic capitalist order. It was to this aspect of the Party that Connolly invested his time in the most, aside from propagandizing.

The ISRP faced early challenges which boded ill for the future. Some of these problems were avoidable and the product of internal ideology. An early example of internal ideology having a negative political impact was a tendency to see issues surrounding republicanism as a competition for political purity.

Connolly saw the Home Rulers, the political party which was generally comprised of upper-middle class Irish businessmen, as the antithesis to republicanism. Home Rule kept Ireland within the United Kingdom, and subject to the Kingdom’s laws, while allowing for some independence in government, similar to Scotland in scope. The alliance of republicans with Home Rulers, in this context, was a betrayal of republican values, and allowed Connolly to make the polemic argument that only the ISRP truly represented the spirit of revolutionary republicanism in Ireland. The ISRP got over its disgust with the republican parties for their right-wing alliances, but only due to political expediency. It is hard to imagine that the problems of the later ISRP did not have some of its roots in this type of unbending partisanship.

The collapse of the ISRP can be traced to divisions within the organization and the antagonism between Connolly and founding member Edward Stewart. Connolly’s style of governing the party, and his trip to America in 1902 to shore up support and establish ties with the IWW, exacerbated already existing problems in the organization. On Connolly’s return, the issue of appropriation of party funds for rent hardly masked the competing visions for the party of Stewart and Connolly.

Connolly believed that Stewart was trying to steer the Party in the direction of a reformist party, one which would work within the capitalist system to solve it problems without changing the underlying structure. This was an accurate perception of the greater division in the Party, between ‘moderates’ and clear cuts.’ The Party split largely down those lines in April 1903, and this was the death blow. The ISRP stayed a nominal organization until February 1904, but the separation of the two wings, and their inability to see eye to eye, had already broken it almost a year before.

The ISRP had disintegrated as a political party and socialist organization. At most, its membership had numbered less than one-hundred. The collapse was due to the usual myriad factors that accompany the dissolution of political movements and parties which lack both the financial support of the capitalist establishment and the popular support of the public. The constant friction between Connolly’s vision of the future of Ireland and the vision of Edward Stewart led to political infighting and sectarianism in the ranks. The Party’s demise led to a general malaise for Connolly. He traveled to the United States in an attempt to develop ties with socialists and unions there, and to escape the crushing feeling of defeat that the ISRP’s collapse had engendered.

Labour in Irish History and Connolly’s Brand of Marxism

On Connolly’s return to Ireland in 1910, he published his pamphlet Labour in Irish History. The work was a call to arms to the Irish working class, contextualizing the independence struggle and exploitation of the country in the broad terms of the history of capitalism. It was, as Connolly said, “not a labor history of Ireland, but a history of labor in Irish history,” and could properly be called a work of political economy.

Connolly addressed the Irish people as comrades in a class struggle that had its roots in the relationship of the aggression of Britain and the acquiescence of Ireland. He believed that the solution lay not only in the independence of Ireland from Britain but also in the rejection of the capitalist social relationship which was at the root of economic and political inequality within the countries’ relationship. The capitalist exploitation and colonial subjugation of the Irish by the British, Connolly argued, was at its root as much a product of an economic system that dehumanized and devalued the working class as it was a product of the British imperial aims and dreams.

Labour in Irish History drew on the work of Marx, not only from his analysis of the Irish situation, but also in the Marxist influence on Connolly’s singularly leftist perspective on economic and political issues within the liberation movement in Ireland. Marx’s influence is felt throughout — Connolly refers to the historical exploitation of the Irish in decidedly Marxist terms and places the Irish economy firmly in the Marxian analysis of capitalist history that was so clearly crystallized in Capital. Without Marx’s call to arms of the proletariat and intellectual alike in both Capital and The Communist Manifesto, it is likely that Connolly’s analysis of the Irish labor relationship would, all other things being equal, have been quite different in tone. Connolly’s Marxism was the driver for his perspective on Irish labor history.

Connolly lays out an inexorable history of the capitalistic relationship between Ireland and England in Labour in Irish History. He describes the ways in which the Irish people have been manipulated into accepting and participating in the institutions that oppress them. He tells the stories of those who tried to break the grip of British rule, only to fail for lack of support or betrayal by a working class that did not understand who their allies really were.

Connolly’s aim in his pamphlet was to tell the poor of Ireland who their true enemies were: the British ruling elite. It is easy to recognize this thread that goes throughout the work. As Connolly wished for the working class of Ireland to rise up by itself and cast off the oppression of the British, the identification of class enemies and unspoken call to arms was the premise of the pamphlet. Connolly’s uncompromising socialism, and his absolutist streak pertaining to the defeat of capitalism, is evident throughout his writing.

The connection between Labour in Irish History and Connolly’s experience in the ISRP is not hard to determine. The stories of strife in and the economic materialism of the pamphlet are all designed to speak to the Irish worker and let him or her know that political movements are empty without attention to historical bases of inequality and exploitation. The pamphlet warns the reader of the impotency of political movements that only offer political solutions to material problems within capitalism.

The subtext of revolution is not hard to grasp, nor is it hard to understand that Connolly was still jaded on political activism after his experience in the ISRP. Connolly may not have mentioned the ISRP in Labour in Irish History, and the historical scope of the book and the relatively recent dissolution of the ISRP would have made it difficult to do so. His analysis of the failings of previous socialist and liberation movements, and their roots in the political process, indicates his continuing frustration with the problems of organizing and maintaining a political organization from the ISRP.

The context of Connolly’s writing of The Reconquest of Ireland and his involvement in ‘The Rising’ has its roots in Irish political history and the specific situation of Ireland after 1910. Home Rule, which has been discussed above, was formally introduced as the next stage in Ireland’s political governance to take place in 1914 by the British government. It did not take effect due to the War. This was only the latest in a string of broken promises designed to placate the Irish republican movement by the British, and proved to be a mistake that would eventually lead to independence in the long term, and ‘The Rising’ in the short term.

John Redmond, who had secured the promise of Home Rule from the British and was the head of the Home Rule Party of Ireland, was seen as the Irish political representative of a pragmatic independence movement. Redmond’s position in the more conservative mainstream of Irish politics, and his willingness to compromise republicanism for a modicum of independence, placed him in the role of political enemy for Connolly and like minded leftists.

Two consequences followed the Home Rule independence compromise for Connolly. First, he formed the Irish Labour Party to act as counterpoint to the compromised Home Rule Party in promoting Irish independence. Secondly, he wrote The Reconquest of Ireland as a rebuke of reform within the capitalist system for Ireland’s independence and took part in The Easter Rising.

The Irish Labour Party

The context of his writing of Labour in Irish History, and his experiences working with the ISRP, led Connolly to form the Irish Labour Party with James Larkin. Larkin was a large man — a dockworker — whose leftism mainly took its form in his push for labor power and militant, radical unions. Larkin was an imposing figure, both physically and ideologically, so much so that Connolly privately expressed displeasure and discomfort at the possibility of a ‘cult of personality’ within the Labour Party based around Larkin. Connolly’s place as socialist intellectual and brains of the Irish left, as well as his experiences with Edward Stewart in the ISRP, may have led him to fear the more loud, charismatic, and dominant personality of Larkin.

Despite these fears, Connolly realized that, pragmatically, the benefits of a socialist labor alliance trumped whatever reservations he may have had of the outgoing personality of Larkin. It should also be noted that although Connolly may have expressed these fears, they were largely relayed in private and had little if any effect on his decision to ally publicly and enthusiastically with Larkin in forming the Labour Party. The more muted and pragmatic reaction of Connolly was in part due to the harsh realities of politicking he had learned from the dissolution of the ISRP.

Connolly’s role in the Labour Party was less based in agitation and propagandizing than it had been in the ISRP, although he did not change his politics. As within Labour in Irish History, the excesses of youth in his political activism had tempered his approach to reaching the people, but not his message. The Labour Party was formed in 1912. In 1914, Larkin, its leader and de facto head, was stripped of elected political power due to his criminal record, causing him to leave for America, and opening the door for Connolly to take control. Working within the given political system, Connolly used his newfound power to address the problems of capitalism he saw writ large in Ireland and the world. The period was a tumultuous one.

The more success the Labour Party had in challenging the status quo, the more repression it faced. Larkin was out of country. Connolly’s revival of his Socialist newsletter was banned. Everywhere Connolly turned, the forces of capitalism were aligned against him. The Unionist merchants and their more powerful patrons in the colonial government put pressure on his political base and squeezed the workers for ever more concessions. The Great War, as it would be known in the decades preceding World War II (and will be known within this paper, or as ‘the War’), was on the horizon. Irishmen would be drafted by the score to go fight in a war that was clearly, to Connolly and his comrades, a war of capitalist attrition in which there was no good side to be on.

The Great War and The Reconquest of Ireland

The Great War was seen as a war of capitalist nations vying for placement within the economic system by most on the left, and Connolly and the Labour Party were no exception. Larkin agitated from afar to put the war in its perspective, as a battle between colonial powers bent on warring over exploitable resources. Connolly agreed, calling for Irishmen to reject the taking up of arms and to refuse to fight a war for the same British imperialism that was the bane of the Irish existence. Some perspective is important for this stand: there was no Soviet Union for these men to look to as opposed to the capitalistic order, and no alternative to the imperialism of the capitalist powers of Europe at the time.The powers of the world were economically ideologically united.

What Connolly and Larkin were endorsing as a course of action, a refusal to fight in the war, was treasonous. While this sort of treason to the modern day reader may seem like activism, within the political society of the early twentieth century in Western Europe, there was no institutional support for such a position.

The road to Irish revolution was built on the foundation of Irish resistance to the War. Many Irishmen went to fight for the British Empire in a war that those on the left, such as Connolly and Larkin, believed was an avoidable war that would have no positive consequences for the participants other than the imperial victors. In addition, the influx of Irish soldiers into the war effort was not met with any concessions to the nation by the British. The possibilities of independence, or simply a more independent Home Rule, were not even entertained by John Redmond, the Irish de facto leader of the republican establishment. The missed opportunities to push for concessions and recognition, and even the opportunity to reject conscription were not seriously taken into consideration.

Redmond’s tenuous political position as head of the republican movement and Home Rule required tough decisions between the interests of the Irish and the British. The decisions generally favored the British, who had the power and organization to enforce their demands the Irish lacked. In the face of domestic political upheaval and the war, Connolly joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood and began to help to plan for an insurrection. He also published The Reconquest of Ireland.

The Reconquest of Ireland is a description of the problems of late nineteenth century capitalism in Ireland and a call to political and revolutionary action directed towards members of the Labour Party and the working poor of the country in general. Connolly states openly in the very first sentence that, in order to reach the goal of setting a course of action, one must understand the historical, political, and economic factors behind the situation at hand.

Where Labour in Irish History had been a broad and general view of the country’s misery throughout the course of imperial capitalism, and was more of a historical work, Reconquest addressed the political economy of potential Irish independence. Where Connolly was leaving the reader to their own devices to choose the way forward in Labour, in Reconquest he was directly calling for the rejection and destruction of capitalism by a coalition of the intellectual and working classes.

If Labour in Irish History was a product of Connolly’s experiences in the failure of the ISRP to reach the greater Irish public, The Reconquest of Ireland was a product of the challenges Connolly faced in his opposition to the war in 1914 and 1915. Having explained to his readers in Labour that their situation was due to the capitalist exploitation of British imperialism, in Reconquest Connolly called for the working class of Ireland to rise up and throw the English and its capitalism out of the country. The tone was martial and militant, and the emphasis was on action, not education.

In short, Connolly had undergone a change in his political analysis of the solution to Ireland’s situation. Labour had educated the Irish working classes to the identity of their true enemy, capitalist imperialism, which took the form of the British Empire. Reconquest was an explicit call to action to overthrow and replace that enemy.

The evolution of Connolly as a revolutionary is evident in the tone of Reconquest. The exploitation of Ireland’s resources and labor is put in terms more amenable to insurrection. Labour was a historical accounting of the dual rise of capitalism in England and its effect on Ireland as a colony, and left the reader in a position to understand the problem and see the inadequacy of reformist solutions. Reconquest addressed the reader in terms of the present state of the Irish plight.

The idea behind Reconquest, as opposed to the earlier Labour, was to convince the working class of their ability to effect change by organizing. Connolly believed that the division between nationalism and socialism would be mended once the working class saw the two interests were not oppositional. Wedding the two purposes was the mission to which he would give his life.

The Rising

Connolly believed, as did a number of his compatriots in the IRB, that the Great War would hamstring Britain’s ability to respond to an Irish push for independence on the battlefield of Dublin. In this estimation, Connolly and the face of the IRB, Patrick Pearse, urged revolution in 1915.

This was a mistake.

The British were in no mood to brook any insolence from their colony while they fought a land war on the continent. The precedent that not responding to The Rising would set for the British Empire was one they were not willing to set. When Pearse, Connolly, and their compatriots launched the rebellion on April 24, 1916, they did so under the auspices of the newly formed Irish Provisional Government. The IPG had Pearse as President and Connolly as Vice President. Their legitimacy would depend on the result of their rebellion.

The Rising was met with fierce and swift retribution by the British, resulting in the capture and execution of the ringleaders five days after the first shots were fired; Connolly among them. Connolly was mortally wounded in the short lived rebellion, and was nearing death when the British dragged him off to his cell. Soon thereafter, he was strapped to a chair to hold him up (his wounds precluded him from holding himself up) and shot to death in the Kilmainham Prison yard.

Connolly’s importance to the rebellion and revolutionary thought in Ireland was not missed by those in power. The mouthpiece of the capitalist class, The Irish Independent, sought vengeance and blood for the insurrection, only ending its campaign for executions once Connolly was in the ground. The campaign for republican revolution on the part of Connolly had ended without any tangible results, and had lost one of its leading lights.

The Rising was a doomed attempt by the IRB to garner support for a full-fledged rebellion across the country. The rebels managed to hold off the British military for five days, but they were inevitably defeated and arrested. Connolly’s arrest was almost pointless, he had been mortally wounded in the fighting and was dying; but as the Vice President of the Provisional Government, and as an agitator in Irish politics for over a decade, he had to be killed as an example.

Furthermore, as was realized by both Connolly and his deathbed surgeon, his refusal to bend to the imperial British and recant his radicalism ensured his demise at their hand. Connolly had compromised once before — by forming the Labour Party, he had necessarily accepted the primacy of Larkin and the possibility of a cult of personality as a fair trade for the movement. But there was no chance that any compromise with the hated British Empire would com, even with his limp body desperately hanging on to life.

Conclusion

Connolly’s evolution from socialist agitator to martyred revolutionary was one that took over a decade, and was the result of the many frustrations, false starts, and repressions he faced in his opposition to capitalism. In his two pamphlets, as well as in his work as de facto head of the ISRP and founding member of the Labour Party, the growth of a radical is apparent. His faith in the ability of the political system to effect the necessary change that he felt was needed in Ireland was shaken by the factionalism of the ISRP. Labour in Irish history was his attempt to alert the people of Ireland to their real enemy — capitalism. The idealism and faith that Connolly had regarding the working class, which had been a driving motivator for the ISRP, also led him to form the Labour Party in spite of his previous political experiences.

The repression that developed as a result of his political success, and the urgency brought on by the War, forced Connolly to consider extremist measures to ensure the liberation of Ireland as a nation and a people. At a time when the Labour Party’s leadership fell on his shoulders, after Jim Larkin was politically deposed and exiled to America, Connolly steered the organization towards heavier propagandizing. This new approach towards political organizing and agitation was met with further repression as his paper was shut down.

The Great War and the crackdown on dissenting views of its legitimacy, in combination with the denial of even the mild independence of Home Rule, sealed Connolly’s views on revolution. Politically, his avenues of change were closed. The only alternative he could see, as Reconquest strongly hints toward, was revolution. Revolution, in the mind of Connolly, would join together those whose interest was in liberation with those whose interest was in rejecting capital, and would expose the enemy of British imperial capitalism to the masses.

Ultimately, Connolly’s interaction with the power of imperial Britain in the early twentieth century was typical of the challenges inherent in resisting the system of capitalism. When he was merely a nuisance, he was allowed to flourish, especially since the ISRP lacked the organizational wherewithal to effectively oppose the capitalist order. When Connolly became a threat, he was neutralized and repressed. The Labour Party and newspaper had the ability and potential to gain a following and influence the collective consciousness of the working class. This potential was squashed by political means in denying elected power and censoring the paper. Capital will use the state to clamp down upon those who defy it.

Finally, Connolly used violent revolution to try to change the power structure of colonial Ireland and inspire the country to rebel. This move, which was a grave miscalculation, was met with the full force of the capitalist state, and ended with Connolly’s death. He was too ideologically pure to buy, too persistent to block, and too troublesome to let die without sending a message. His role in Irish republicanism is the role of a martyr. The Rising influenced the drive towards independence for Ireland. James Connolly’s place in that history, and the history of socialist revolutions, is that of ideological hero.