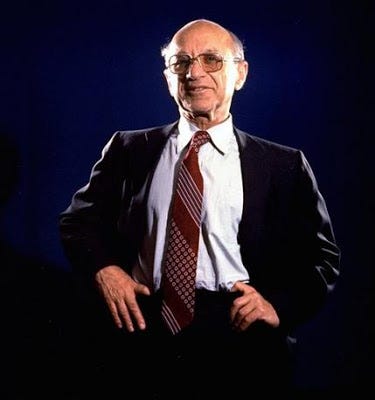

Milton Friedman Attacks Marx, Fails.

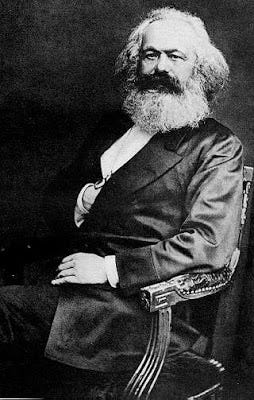

Milton Friedman takes a swipe at the Karl Marx’s theory of value and exploitation in his Capitalism and Freedom. Friedman’s attack on Marx’s work is predictable in context of his book, but is, like most else he says, a mixture of theoretical inconsistency and outright lying. The main thrust of the philosophical aggression of Mr. Friedman towards Marx in this specific case is that Marx’s theory of surplus value is a theory of accumulated value, and thus any exploitation is on the labor of yesteryear. Friedman’s attack on Marx is either a complete lack of understanding of Capital’s theory of surplus or a blatant misrepresentation in order to continue to promote the libertarian thesis of Capitalism and Freedom.

“Labor is ‘exploited’,” Friedman says, “only if labor is entitled to what it produces” (Friedman, p. 167). Friedman disagrees with this notion, arguing instead that the capitalist who invested in such production is the entitled one to the product. This may be true in our present legal definition, but what Marx argued, and Friedman knows quite well, is that such a state of affairs is not only unfair, but based on exploitation. Let’s take a look at what Marx says on the matter of labor’s rights to production. Marx established labor itself as the commodity of the worker purchased by the capitalist, who consumes this commodity by “setting the seller of it to work” (Marx, p. 283). Production is the act of labor adding to the value of whatever resources and previously purchased commodities, themselves in the form of raw material, by transforming them through said labor into specific articles. “The fact that production of of use values, or goods, is carried on under the control of the capitalist and on his behalf does not alter the general character of that production” (ibid., emphasis added). In other words, the character of production and labor is the same no matter who is in control of the labor and no matter on whose behalf it is done.

The commodity of labor, consumed by the capitalist, is added to the commodity of raw materials and adds to their value. But Marx makes very clear that the only value which is added in this regard that can be used by the capitalist to make a profit is the labor of the worker. The raw materials only gain in value when labor is applied to their substance and they are transformed into more valuable commodities with use values unrelated, or at least increased, by said labor. So it is labor itself which valorizes, to use Marx’s term for the addition of value, the original material. For the capitalist to make his desired profit, the only value he can exploit is that of labor. So by paying the seller of the commodity labor less than the labor is worth, the capitalist turns his profit on the productive labor of others. This is exploitation proper, the underpayment or reward of the labor of others.

Friedman and his libertarian ilk would argue that labor is not exploited, nor entitled to that which it valorizes in its application, because without the intervention of the capitalist, all this labor would have nothing to do. One can visualize the libertarian ideal as a great number of poor and stupid workers wandering about with nothing to do with their commodity until the benevolent capitalist, with a smile and promise of paradisal benefit to performing labor under his auspices, appears on the scene. A nice apologia for the capitalist process, but one with severe problems. First, the capitalist class comes not from any benevolence. The capitalist class is made up of, for the most part, those who had either the capital to begin with at the onset of capitalism due to feudal exploitation, or those who have had success in the new game of exploitation of capitalism. These are not the motivations nor the actions of the altruistic. Secondly, the concept of the retardation of society before the interceding of the greed-inspired capitalist class is simply untrue, unless one defines progress as environmental destruction, overpopulation, starvation and worldwide anguish on the part of those not lucky enough to be in the top tier of the exploitative nations.

Friedman makes another leap of logic by defining capital itself as the result of past labor’s surplus value, which is legitimate, and then by demanding that if we are truly to repay labor’s exploitation, we must deal with these past transgressions instead of applying our sense of justice exclusively to today’s labor market. This argument is a fallacy. To assume that the hypothesis that all capital gain is from the exploitation of labor directly leads to, as Friedman puts it, “that past labor should get more of the product” (Friedman, p. 168), is deceptive at best. The Marxian analysis, and indeed the leftist analysis, of the exploitation of today’s worker is that it is related to the past exploitation only in so far as that past exploitation has cemented the power of the capitalist class and made it easier to provide a sociological apologia for continuance of the exploitative practices. It does not mean that the past exploitation should be rewarded by elegant tombstones, which is Friedman’s dig at Marx in the final line of his attack (and likely written with the smirk that always adorns his picture). Instead, the leftist believes that the history of exploitation and seizing of the surplus value produced by labor’s under-reward is no excuse for the continuance of such activities now.

Milton Friedman attempts to mock and make light of Marx’s theory of exploitation and labor commodity surplus production, but his argument lies in a misreading, at best, of Marx. Where Friedman asserts Marx believed exploitation of the worker was based on some socialist manifesto of equality, Marx was simply observing the manufacturing process of capital and drawing his conclusions. That his conclusions resulted in the exploitation of the worker and the robbing of value by the capitalist may be intolerable to Friedman, this does not mean they are incorrect. Marx’s interpretation of the labor process is still as legitimate and powerful today as it was a century and a half ago, when he wrote his masterwork. One cannot say the same for the ideas and ideology of Milton Friedman.