Keynes and the theory of crises

The current crisis of capitalism our country and world is going through was not one which could not have been foreseen. All one had to do was to page through John Maynard Keynes’ The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, read the section of the chapter, “Notes on the Trade Cycle”, concerning crises. These five pages sum up succinctly not only the current financial meltdown, but also are indicative of the problems that our economy has been facing since 1973, the year the post-World War II sustained boom ended. John Maynard Keynes’ analysis of crises was prescient and still sustains its legitimacy.Keynes defines a crisis as “a sudden collapse in the marginal efficiency of capital” (Keynes, p.315), this marginal efficiency of capital being “the rate of return expected to be obtainable on money if it were invested in a newly produced asset” (Keynes, p. 136). This is to say, the marginal efficiency of capital is is the amount of profit expected from the use of said capital in new investment. A crisis, then, is the result of a sudden and violent change, in the negative direction, of this marginal efficiency. A crisis is not, to be clear, a lower than expected rate of return on investment and capital expenditure, though this could precipitate a crisis. Instead, a crisis involves a lower than expected prediction of the future returns of investment and capital expenditure.

Keynes point out that crises are almost always preceded by booms, this, in effect, is the extreme of the trade cycle. A boom usually begins with a higher than usual marginal efficiency of capital, and this can be due to a myriad of related or unrelated factors, be it an innovation that spurs investment, high consumer demand, or a speculative bubble, to name a few. The boom will lead to high employment and consumption, which in turn will feed investment, and all will be right in the world (if one sees the world’s perfection as capitalist success). “The later stages of the boom,” says Keynes, “are characterized by optimistic expectations as to the future yield of capital-goods sufficiently strong to offset their growing abundance and their rising costs of production and, probably, a rise in the rate of interest also” (ibid.). Keynes saw how the boom’s maturity maintains a myopic view of future production, and how this view of the future perpetuates a belief that no matter what realities of capitalism lies in the future, the marginal efficiency of capital will continue to thrive.

Over-optimism is a dangerous mentality, especially in matters of economics, because it is always destined for a crash back to reality, a crash that can, in its pessimism, result in a mentality as negative as the optimism was positive. As Keynes says, once “disillusionment falls upon an over-optimistic and over-bought market, it should fall with sudden and even catastrophic force” (Keynes, p. 316). The market, to be clear, is over-bought in this case as a result of the ignorance and optimism of investors who simply wish to get their share of the ever-growing pie. The crash also results, after the decline in marginal efficiency of capital, in an increase of liquidity-preference, Keynes’ term for the preference for cash reserves as opposed to stocks or capital as the makeup of ones money. Corresponding with these two factors tends to be a rise in interest rates, interest rates being the only way one can profit in a contracting economy, which “may seriously aggravate the decline in investment”, rendering “the slump so intractable (ibid.). While cutting the interest rate may seem an attractive fix for the crisis, “the collapse in the the marginal efficiency of capital may be so complete that no practicable reduction in the rate of interest may be enough” (ibid.), a prediction of Keynes’ that has been borne out in light of the Federal Reserve’s continual attempts to reverse this recession (or depression) by doing just so.

A crisis cannot be overcome, despite the protestations of the neoclassical school of economics, until the optimism that is so essential to the marginal efficiency of capital returns to the market. “This is the aspect to the slump.. which the economists who have put their faith in a ‘purely monetary’ remedy have understated”, and it is “insusceptible to control in an economy of individualistic capitalism” (Keynes, p. 317). The neoclassical school of economics argues that such concepts as confidence are inapplicable to the working of the market, instead arguing in favor of an economic reality that is based on perfect information and supply and demand. Why, the neoclassical argument goes, should there be a crisis of confidence when demand exists and supply can be provided? Why would there be a problem when everyone has the potential to invest and profit from the market? And why, they furthermore postulate, should anyone unemployed have any trouble getting a job? There are jobs, and if the unemployed will not work them, this is the individual’s problem, not a problem or crisis of capital. It is an argument that fails when it encounters reality, of course. Investment and marginal efficiency of capital are not subject to mechanical workings of theory, they play out in the real world, where human nature has more than a hand in determining activities. As might be expected, the neoclassicist can no more understand this than understand Karl Marx- both offend his senses with their logic.

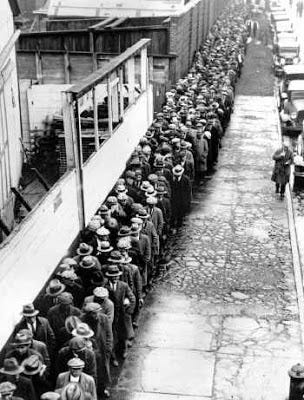

“The disillusion” of confidence comes, Keynes says, “because doubts suddenly arise concerning the reliability of a prospective yield” (ibid.). If the future gains of one’s capital are in doubt, or in jeopardy, or even simply at a lower level than before, doubt sets in, followed by panic. Once the doubt begins to arise, its spread is inevitable, like wildfire. The doubt is followed by a sharp decrease, even into the negative, of marginal efficiency of capital, and at this point in the crisis, says Keynes, the only recourse is to wait. Time heals all wounds, and the economy’s lacerations from a decline in confidence is no different. “At the outset of the slump there is probably much capital of which the marginal efficiency has become negligible or even negative” (ibid.). This fall in marginal efficiency feeds upon itself, in a spiral of insecurity that exacerbates until there is nothing left of the former confidence which powered the economy prior to the fall. It is at this point that the rebuilding begins.

Over time the crisis must end. Humanity must consume to survive, and thus, to maintain the level of our species’ population on the planet, production of an industrial nature is needed for this survival. There is an interval of time “which will have to elapse before the shortage of capital through use, decay and obsolescence causes a sufficiently obvious scarcity to increase the marginal efficiency” (ibid.), in other words, after a period of time, production must have an infusion of fresh capital to continue to produce, due to the ravages of time upon the instruments of production and the drying up of older funds. In addition to the decay of capital put forth before the crisis, “the sudden cessation of new investment after the crisis will probably lead to an accumulation of of surplus stocks of unfinished goods” (Keynes, p. 318), which will necessarily have to absorbed, at a loss, into production. This absorption, when over, will produce such a sense of relief in capital that it, combined with the end of old capital due to decay, requires a renewal to continue the workings of industrial production, at which point the recovery has truly begun.

Today’s crisis has its roots in Keynes’ analysis of the decline of marginal efficiency of capital, though it is certainly a different world and thus a different type of crisis than Keynes ever could have envisioned. Keynes’ vision of the crisis sees the marginal efficiency of capital as applicable to industrial production- not as the marginal efficiency of capital to financialization and the creation of money with money, but without creating anything of value. Keynes did see how, “with a ‘stock-minded’ public, as in the United States today, a rising stock-market may be an almost essential condition of a satisfactory propensity to consume” (Keynes, p. 319), but he could not see how the stock market would become the main driving factor of the economy, how marginal efficiency of capital would apply to its ability to asexual reproduction. For the financialization of the economy was a factor Keynes could not have foreseen. The post-war boom was so sustained and powerful, lasting almost thirty years, that it put the notion of the three to five year cycle embraced by Keynes on its head. This boom could only be followed by a bust of an equal magnitude, and no amount of quick fix patches have been sufficient to reverse it.

The economic failure of the past three and a half decades has seen a number of attempts to resolve the problem. These solutions run from the Keynesian notion of more government spending to spur consumption and increase the employment multiplier (give money to the poor to spend and it will, in turn, lead to capital investment to keep up with the new demand) to redistribution of gross income through tax cuts for the rich. The governmental programs which ostensibly assist the least fortunate, in order to increase their consumption and aid their survival, are never funded sufficiently and always balanced by cuts to other social services in order to justify the expenditure. Far more successful has been the cutting of taxes for the rich as a means of redistribution of income lost in the decades long recession. The rich have used their pull in government to create a distribution cycle of income from production that benefits them greatly, at the expense of social programs and in such a way as makes necessary the two-worker household and the doubling of household income to make ends meet. It is a clever means to the end of ever growing profits, even when the pie that is being cut into is shrinking.

The current crisis our economy finds itself in may, indeed, be the final death throes of capitalism as we know it and the final choking gasps of the neoclassical economist as respected intellectual. It is obvious that the laws of supply and demand are insufficient to make up for the lack of marginal efficiency of capital brought on by financialization and globalization, the one being the driver of an economy that has lost most actual productive capacity due to the other. The neoclassical economist assures us that the economy is self-propelled and needs no rules or guidance, yet when such an obvious fallacy is heeded, the result of deregulation is always collapse on the part of the deregulated industry and duplicity on the part of those who contribute to that collapse. Capitalism itself cannot exist without some sort of governmental regulation to keep it in line with its purported goals, that is, capitalism, left to its own devices, will implode in an ever tightening spiral of dishonesty, exploitation and corruption, but when kept in line, relatively, it will take a path somewhat efficient and fair. Keynes tried to warn his fellow intellectuals and those of the ruling classes that their greed would be their undoing, but, as typical, his warnings were ignored and scoffed at, as they still are today in some quarters.

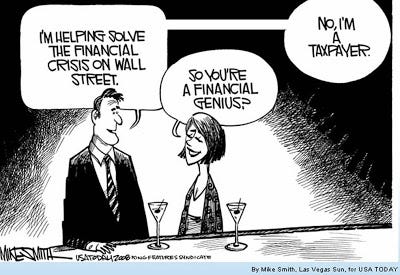

The steps taken to resolve today’s crisis have been predictably lunatic and short-sighted. The United States Congress, instead of providing the lower tiers of society with the necessary capital to relieve their precarious economic position, due to the false inflation of housing prices by the financialized banks, gave the capital instead to those same banks in an alleged attempt to save the economy from crashing. The economy was going to crash, they told us, because housing prices had been so over-inflated, and so many people had taken out loans directly against these over-inflated prices, that the banks were sitting on debt that could not conceivably be paid back. It is almost as if they read Keynes’ theory of the employment multiplier and agreed with it completely, except for the most important part, which concerns the employment multiplier needing to be used in a poorer community to reap the greatest benefits from it. The Federal Reserve cuts interest rates endlessly, and wonders why this is inadequate to solve the crisis, though it is explained above. Finally, the President and Congress pass a stimulus bill intended to provide jobs and relief to those among us who are least fortunate. What the stimulus bill in fact does is provide some money for tax relief to the poor and provides some money for public works, but these admirable achievements are rendered meaningless by the cuts in social programs and tax cuts for the rich. The balance of these factors simply continues the imbalance of inequality and contributes nothing to the social welfare of the country, nor does it provide for meaningful relief from the crisis.

Keynes’ analysis of the crises of capital is accurate and appropriate to today’s economic catastrophe. Keynes sees the factors involved in the creation and continuation of a bust in the very boom it proceeds. Keynes notes the factors, such as interest rates, marginal efficiency of capital and confidence, that create a crisis and also points out that no crisis is forever by pointing out the factor of time. Keynes offers solutions to crises that tend to involve spending by the government on the poor in order to assist those who are least fortunate to consume and subsist. The reasoning behind this is simple- the poor are the masses, and their consumptive power is far greater than that of the rich who, though they may spend more at a time, are so few that their contribution is lacking in comparison. Keynes saw this and warned against doing exactly what our government has done in the bailout and by cutting taxes. Keynes’ analysis of crises is correct and we should do well to heed his warnings for the duration of this hard economic time.