Karl Polanyi, Speenhamland, and the Future of Capitalist Legislation

Karl Polanyi’s The Great Transformation is an instructive text describing the factors which led to the formation of the capitalist state in the middle of the twentieth century. From the transition of the feudal societies of Europe in the Middle Ages to the financial breakdown and post-World War II time period Polanyi was writing contemporarily of, the evolution of the market and social upheaval that evolution engendered has had an incredible effect on the society of the west. One might ask, on reading the book, if Polanyi’s acute sociological analysis of the conditions under which Europe struggled have any bearing on today’s uniquely American financial and social crisis. To truly comprehend the application of Polanyi to today will likely be the task of future generations. One thing, however, is already clear. Polanyi’s investigation into the causes and results of the Speenhamland Laws of England in 1795 shows the dangers and pitfalls of over legislating the welfare of the displaced and poverty-stricken.

Polanyi alleges the Speenhamland Laws came into effect for a simple reason, that the enclosures that precipitated the market economy of modern capitalism resulted in a social upheaval of the established order of feudalism that left many of the poor in destitute and wretched conditions. “The economic advantages of a free labor market”, says Polanyi of the springing up of the wage laborer from the fertile soil of the land-deprived serf, “could not make up for the social destruction wrought by it” (Polanyi, p. 81). With the changing of the social contract that once provided for poor and rich alike, set as the immovable law of god as applicable to the terrestrial sphere, and changing it to mutable and liquid covenant of which nothing was certain, the enclosure movement was truly “a revolution of the rich against the poor” (ibid., p. 37). No longer was the lord or the landed merchant responsible for the welfare of the serf, no longer did the rules of societal responsibility, handed down for centuries in the cultural makeup of Christian Europe, apply for the wealthy and powerful to their subservient and grateful servants. The poor, those who had no right to lording over the communal land and habitat, were losing not only their rights to subsistence but also their shelter. The wealthy, both gentry and merchant, “were literally robbing the poor of their share in the common, tearing down the houses which, by the hitherto unbreakable right of custom, the poor had long regarded as theirs and their heirs’” (ibid.).

With this disruption of the hierarchy and collective expectation of those on the lower strata of civilization came pauperism. The pauper was a member of society devoid of any possessions, capital or usefulness, in other words, the pauper was homeless and without recourse. The continuance of the inexorable march towards the market economy, the birth of capitalism proper as we know it, thrust the poor more towards pauperism. This state of affairs was unsustainable, not to capitalism per se, but to the interests of the nation. The nation could not afford to see so many of its subjects subjected to such an actuality of existence, for this would increase the natural burden of the state, that is, to provide for the people. This may seem confusing on the face of it to those who have been inundated by the reflexively anti-poor and pro-industrialist discourse of the neoliberal school of economics. Having heard the noise machine of the media and those whose power is represented more stringently in our government than the populace endorsing ad infinitum the benefits of the free market, one might surmise that such concern for the welfare of the people is antithetical to the economic and political interests of the state. But this perspective is wrong.

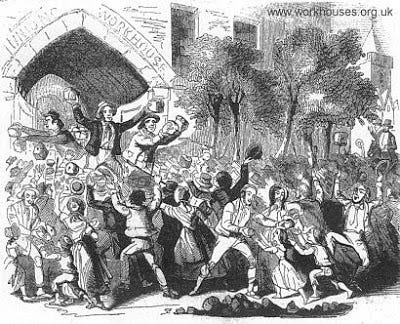

The need for the poor to have at the least a subsistence level of income is the genesis of the Speenhamland Laws. These laws provided “subsidies in aid of wages [that] should be granted in accordance with a scale dependent on the price of bread [it being the staple of survival at the time], so that a minimum income should be assured to the poor irrespective of their earnings” (ibid., p. 82). That is, the laws used the staple of bread as an equalizing price for the intervention- that is, when the cost of bread was one shilling, the family had a guarantee of three shillings a week, thus ensuring the family’s upkeep. The laws were necessary. To offset the threat of revolutionary action by the angry majority of the country who, having seen their livelihoods and homes summarily destroyed in a single stroke, were prone to riot, the Speenhamland Laws were an attempt by the ruling class to stem the flow. It should be noted, also, that the greater interests of the ruling class and the state would be served by such provisions. The ruling class were spared the quelling of inevitable uprising by those who had nothing to lose, and the state would be ensured a maintaining of the bodies needed should war become necessary.

The Speenhamland Laws “introduced no less a social and economic innovation than ‘the right to live’” (ibid.), and this innovation was anathema to the capitalist class. The unprecedented conception of this right resulted in two major outcomes which, each in their own way, would in turn result in the ending of the laws. The first outcome was a sharp decline in the productivity of labor. Though “no measure was ever more universally popular”, the “impossibility of a functioning capitalist order as long as wages were from public funds” made the repeal of the laws an inevitability (ibid., p. 83, p. 85). On the one hand, the vast underclass capitalism had created were happy to see the unfortunate circumstances they had become subjected to balanced in part by a social program that made up for inequities of wages by public funding. On the other hand, the decline of productivity was destined to occur. The aid of wages Speenhamland dispensed was enough to not only supplement the pay of the workers, allowing the employer to drastically cut the pay given to the worker, but also was such that due to that very fact their was no competition of wages, leading to a flat rate of pay. Thus the worker had no incentive to perform his job any better than the next, and as a natural result the quality of work declined. A decline in wages was no problem for the lawmakers and industry. But a decline in productivity was.

Furthermore, the Speenhamland Laws dehumanized the worker by taking away his independence. Poorhouses were horrific cesspools of filth, and though they were provided by the state, their maintenance was given the same amount of attention it usually is, that is, while purportedly to be well funded by the discourse of the politicians and leaders, the truth of the matter was the parishes and communities whose responsibility it was to keep up the letter of the law seldom had the resources to do so and if they did, were flooded with the professional pauper. Even if the worker had the good fortune to be relatively secure in his position of employment, he would always know that his income was not parallel to his performance, no, his income was a subsidy of the state, yet not a subsidy in which he took part, to wit, the state provided his income for him but he had no participation in the working or maintenance of the state, and thus was a victim of charity, not a member of society in good standing. The worker, due to the very laws allegedly ratified for his welfare, was ensnared in a bear trap of insecurity he had stumbled into by circumstance.

The Speenhamland Laws were repealed in 1834, but their legacy lived on. Polanyi argues that the condition of the worker in the nineteenth century, and in a way the condition of society in those years, were defined in many ways by the ineffectuality of the laws and the missteps their passing brought. The problem of Speenhmaland wasn’t the desire to define a minimum of income for the working class, it was the activity of the capitalist state expecting a more socialistic communal spirit when asking the worker to make sacrifices in a cutthroat labor market — a problem we see over and over in history whenever the interests of the poor and rich diverge and legislation attempts to reconcile the two. It’s rather obvious to the observer that such legislation can never work in a capitalist economy. The worker never feels he or she has an investment in the business of society, and the capitalist class refuses to ease up on the exploitation of the underclass though redistribution. The answer does not lie in a libertarian view of an unregulated market, nor in a Keynesian soft capitalism. The answer is a radical transformation of our economic system away from capitalism.