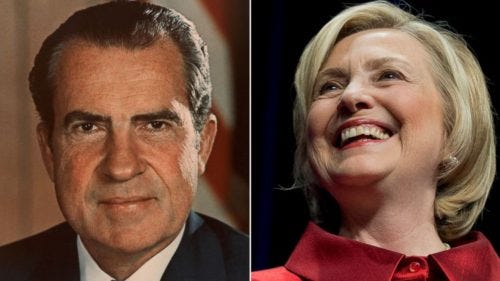

In 2016, Trump is Wallace. Clinton is Nixon.

Regular readers will recognize a bit of an obsession here with the US presidential election of 1968 and how it relates to the 2016 cycle. I’ve written extensively about Richard Nixon and Donald Trump’s similarities in style, how Nixon’s use of the language of the white backlash to the Civil Rights Movement preceded the current white nationalism of the modern GOP… well, maybe I just have an obsession with Nixon and 1968.

Point being, there are parallels here between the US political situation and presidential election in 1968 and that of today. What I’ve been getting wrong, though, is who Nixon most closely analogizes to. It’s not Trump.

It’s Hillary Clinton.

Now this isn’t meant as a judgement of her policies and their relationship to Nixon’s policies (though there’s a lot of overlap). Rather, this is meant to situate Clinton and the race for the presidency in 2016 as they relate to the 1968 election.

Clinton’s current predicament in the primary process for her party- facing a surging upstart from the “fringe” of her party- mirrors Nixon’s push for the nomination of the Republican Party in 68. Both Nixon and Clinton entered the race as prohibitive favorites, each after losing an election eight years before (Nixon lost the 1960 presidential race against Kennedy, Clinton lost the 08 primary to Obama).

Nixon would prevail and become the nominee of his party, and Clinton is assured of doing the same, no matter what snake oil certain Huffington Post writers try to sell you.

From there, Nixon would go on to win the election- and so, I believe, will Clinton. The reason for each victory is largely the same.

It’s the candidate to the right.

Enter Trump. Trump’s campaign for the presidency has relied on the reassertion of white nationalism in the Republican Party, a long held traditional view of the party base that has been held under wraps for years by vague and deceptive language. That language was pioneered by Nixon in 68 as a gentle “dog-whistle” to the white reactionary base.

The dog whistle was necessary to attract more moderate whites who were not as comfortable with the language of white anger as the more conservative wing of the Republican Party and the more reactionary members of the white backlash coalition.

Despite the general understanding of white backlash to the Civil Rights Movement that exists in mainstream sources today, white anger and resistance to integration was also driven by a number of factors other than pure racial animus, such as economic anxiety and the perception (well-earned) of hypocrisy on the part of many of the architects of the anti-segregationist policies of the 1960s.

But for the more extremist elements of white backlash in the country five decades ago, there was George Wallace. He launched a quixotic third party bid for the presidency in 1968 that was based purely on resistance to integration.

The parallels between Wallace and Trump are many; from personality to the protest their rhetoric provokes. But it’s most clear in the unintentional provision of the same service to their respective institutional right wing opponent: cover for mainstream right wing proposals and candidates by not being quite as superficially loathsome.

In the context provided by the more extreme elements of the right as demonstrated by both Wallace and Trump, candidates like Clinton and Nixon look somewhat benign. Sure, they have some wacky ideas and it’s all but certain that the US policy of war, death, destruction, and the annihilation of workers’ rights will continue under their presidencies.

But at least they’re not as crude as their opponents.

This election is taking place in a very different year and with a different political culture than 1968. There will be no mainstream left alternative to Clinton, the Bernie Sanders campaign has ensured no movement to outflank Clinton will survive after the Vermont Senator’s endorsement of the Democrat. It will instead be right against right, two members of the ruling class competing against each other to see who gets to sit in the White House.

But the central idea here, that Clinton and Nixon are similar and that their successful runs for the presidency were and will be predicated on the more extreme candidate to their right, is the right one.

Let’s hope for a real left alternative as soon as possible.