Gay New York- a study

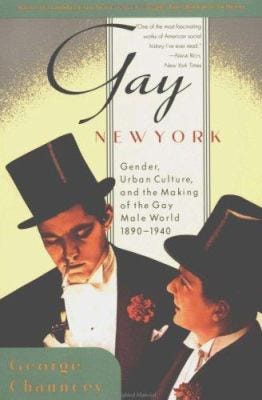

George Chauncey’s Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World 1890–1940 is a clear, engaging and in depth study of the gay world of early twentieth century New York. Chauncey’s book opens and invigorates the debate over gay identity in the modern world by defining gayness as gendered first, then, later in the time period covered in the work, as specifically related to sexual objectification, that is, as related to one’s sexual desire. The effect of Chauncey’s work can be seen in two articles, one written a year before, by John D’Emilio, an update of a lecture given in 1979–1980, “Capitalism and Gay Identity,” and one written five years after, in 1999, by Steve Valocchi, “The Class-Inflected Nature of Gay Identity.” Both articles approach the issue of gay identity and its evolution in the twentieth century through the lens of capitalist society, and one can easily see, as will be demonstrated below, that Chauncey’s study of the topic has had an effect on the scholarship.

John D’Emilio’s central premise in “Capitalism and Gay Identity” is that before the advent of capitalism as the central defining economic order, the idea of a “gay” identity did not exist at all, and it was only after the concept of free labor became widespread that the identity and political organization of “gay” people came into existence. D’Emilio argues that before capitalism became the economic order, those who felt homosexual urges were not “gay” as such, but rather performed at times certain sexual acts that involved members of the same sex. These individuals then settled into the nuclear family as a way to maintain survival through propagation of the species. Only with the freedom of capitalism, D’Emilio argues, was the individual able to break free of the familial unit and not only express himself as himself but also to individualize and valorize his own sexuality as sexuality itself, as opposed to a means to the end of procreation. “By the end of the [nineteenth] century, a class of men and women existed,” says D’Emilio, “who recognized their erotic interest in their own sex, saw it as a trait that set themselves apart from the majority, and sought others like themselves.” So, if we accept D’Emilio’s view, homosexuality was not a defining factor in one’s life before the advent of the capitalist epoch, at least in American society, and we can trace the beginnings of the identity to that point.

Valocchi takes a different tack, placing gay identity in the context of social controls that are capitalist, but specifically class based. He relies heavily on Chauncey’s work, using Gay New York’s scholarship on the shifting nature of homosexuality in the city to invest in a deeper analysis of class based differences in approaches to the gay identity politics of New York at the turn of the century and beyond. Valocchi, in sum, argues that the idea of a separate homosexual identity, and indeed, the entire hetero/homo binary, is a result of social controls put in place by the dominant culture. The evolution of people who had gay tendencies to an overarching set of defined “gay people”, Valocchi asserts, was a product of middle classed ideas of sexuality defining one’s masculinity and femininity first, and setting up boundaries within that binary, and, secondly, by defining the homosexual side of the binary as sexual object choice, rather than gendered. The gender order, which is an order of power, expressed in patriarchy, aligns masculinity with men, legitimizing male dominance, and when one’s gender performance does not align with one’s biology, as in the case of the campier, more flamboyant gay men, it upsets the order. Therefore, the identity of the gay man had to be differentiated from the straight man, and the hetero/homo binary of hetero-normativity was born. Thus, for Valocchi, the idea of homosexual identity within the social order is a maintaining of the dominant culture’s masculinity by excising the homosexual from the heterosexual and excluding them from the dominant culture.

It is between these two analyses, which, despite their differences, are rather complementary, that Chauncey’s work’s impact can be seen. Gay New York is preoccupied with questions of gendered and objected gay sexuality, devoting chapters to both the effeminate “fairies” and “pansies” as well as the more masculine “trade” or “wolves.” Chauncey tells the reader that the idea of a hetero/homo binary in the turn of the twentieth century was almost non-existent, and that, instead, as far as sexuality was defined, it was more defined by gender. For example, on page 81, he tells the story of a young man sexually dominated by an older man- the young man, feeling he has been feminized, is ashamed, the older man has lost none of his masculinity, and, in fact, may have gained some prestige from his sexual domination. It is only later on in the century, particularly after Freud, that homosexuality is seen as not sexual inversion, where the man desires to be penetrated, and is therefore desirous of being a woman, feminine. Instead, homosexuality was seen as being a result of one’s sexual object choice, the desire to have sex with one of the same sex as opposed to (or alongside) one of the opposite sex. In fact, sexuality as a whole was changed by this sexual object choice dichotomy.

D’Emilio’s argument that capitalism, undermining traditional familial structures by the freeing of labor, gave rise to the kind of individualism that would foster sexual freedom, is both undermined and supported by Chauncey’s subsequent scholarship. On the one hand, simply ascribing the rise of the homosexual identity in the early twentieth century to capitalism is far too facile in light of Gay New York. Chauncey’s study of evolutions in thought and identity for gay men shows the complexity of the subject. Identity meant different things in different classes, walks of life and ethnicities. Culture was both affective and effected by the gay culture of camp and the “fairy.” The “pansy,” or “fairy,” was a noticeable and open part of New York nightlife by early on in the twentieth century, using effeminacy to define himself as different from his male counterparts whose masculinity was perhaps more well defined. (50–51) Fairies and their men, known as “trade” or “wolves,” were at times so utterly unashamed and normalized in their relationships that they saw no need to deny or to hide them. (87) This type of open identification as different is perhaps due to a new economic order, but the openness of these relationships certainly suggests a deeper cultural tolerance that cannot have begun as recently as D’Emilio claims. On the other hand, D’Emilio’s work in establishing the advent of modern homosexual identity is supported by Chauncey. Both authors delve into the gay world of New York City in the early twentieth century, and although for Chauncey it is the basis for a large book as opposed to D’Emilio’s article, the similarities in subject matter are striking, different findings notwithstanding.

Five years after Gay New York’s publication, Valocchi addresses the subject of gay identity, and in his article we see the effect of Chauncey’s work, as Valocchi uses the historiography of Chauncey to further his thesis. The idea of dominant culture enforcing exclusionary sexual binarism is a result of capitalism’s need to alienate people from one another in the quest for profits and labor. Alienation bred a new grouping of people as “homosexuals,” who were so named not because of their perceived gendered inferiority, but, as described by Chauncey, because of their sexual object choice. This difference in identity gave more diversity to the gay identity and created a new social class, albeit one that mostly had to live in the shadows. The effect of Chauncey’s work on Valocchi cannot be understated. Gay New York is cited no less than fourteen times over the the fifteen pages of Valocchi’s article, and Chauncey’s work on not only the historical markers of gay identity in early twentieth century New York but also what makes gay identity in the first place is integral to Valocchi’s study. Perhaps it is best to allow Valocchi to speak for himself, showing the place Chauncey’s work has in the study of gay identity and how that identity changed: “Historical research on homosexuality documents a shift that occurred during the first half of the twentieth century in the notion of ‘the homosexual,’ from a gendered definition (i.e., a biological man acting in sociologically feminine ways, a biological women acting in sociologically masculine ways) to a definition unhinged from gender and hinged to sexual object choice (i.e., being attracted to members of one’s same-sex [Chauncey 1994]).”