Friedrich Von Hayek and the Fallacy of Analysis

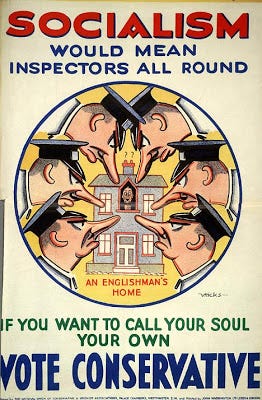

Friedrich Von Hayek argues against the dangers of a totalitarian government in his classic work The Road to Serfdom. Hayek’s thesis, that socialism alone leads inevitably and inextricably to oppression and fascism, is problematic and does not stand up to the test of time or logic. It is instructive to realize Hayek wrote The Road to Serfdom over sixty years ago, and to take with a grain of neoliberal salt this fact when reading and interpreting the book. Hayek did not predict, for example, or understand, that the same factors of individualism and competitive capitalism he espoused could and would lead to oppressive governance of the sort he associated with socialism. Hayek’s analysis of the dangers of an all-powerful, all-encompassing government loses traction with the reader due to its shaky economic foundation and dubious credibility.

Hayek asserts that the fact that “people who abhor the idea of a political dictatorship often clamor for a dictator in the economic field” and that this displays an ignorance about the facts of economics and its relation to society and life (Hayek, p. 124). Hayek has a point. An abhorrence of political dictatorship does not necessarily lead to a correlative aversion to an economic one. It is easy to understand the perceived similarity between the two issues- political dictatorship is generally a method of governance that uses brutality to further its aims, and an economic dictatorship, a dictatorship of, as Hayek defines them, “planners”, uses a type of brutality itself in order to further its aims. The differences are stark, however, between the two. Brutality of the political dictator against the populace is a physically and personally violent one, while the brutality of the economic dictator is only a violent one in as far as it forces the inequalities of the economy into parity. This forcing of parity may be harmful to the capitalist, but, in the end, it is extremely beneficial to the majority of society. Those who have a tenderness for economic control by the state are not suffering from the “erroneous belief that there are purely economic ends separate from the other ends of life”, in fact, their desire for a more level playing field is indicative of a total understanding of this reality (Hayek, p. 125).

Hayek’s interpretation of the economic man is a curious one, and in its curiousness it displays an elitist misunderstanding of what has become known as the proletariat. For Hayek, the optimal economic situation is that of free market capitalism. And in this system, says Hayek, “so long as we can freely dispose over our income and all pour possessions, economic loss will always provide us only of what we regard as the least important of the desires we were able to satisfy” (Hayek, p. 126). This idea is, at its root, utterly preposterous. Hayek seems to believe that those who have a limited income, limited in this sense as applying to one’s subsistence, can choose how and when to spend this income, instead of discerning that in the real world, when one is limited in one’s income, one has to make difficult decisions about which of the necessaries of survival one purchases. It is not enough to assume that the thing one cannot buy due to these limits is unnecessary for survival. Not that this is anything a man who spent the majority of his life in university would be expected to comprehend, in fact, Hayek holds to the belief that those of the lower classes have so little understanding of monetary actuality, they believe whatever “affects only [their] economic interests cannot seriously interfere with the more basic values of life” (ibid.). Which makes sense, because the poor have no understanding at all of how the economy affects their lives, as opposed to the rich, who feel every shift of the marketplace sharply in their wallet.

“Economic control”, says Hayek, “is not merely control of a sector of human life which can be separated from the rest” (Hayek, p. 127). Hayek maintains that control over economic matters is “the control of the means for all our ends” and that it that it must necessarily “determine what ends are to be served” by society and “which values are to rated higher and which lower” (ibid.). If we are to believe Hayek’s evaluation of economic control and planning, then the more of it we see in society, the worse. In fact, it follows from the hyperbole that economic control by a central authority is tantamount to utter dictatorship, and is the first step in the march towards fascism. But this evaluation of controlled and planned economies is misleading at best and deception at worst. When the market is left to its own designs, the result is a turn of events that benefits those in charge of the means of production, the capitalists. With a planned economy, it is true, the determination of the benefit of the economic charge is in the hands of the government, but the government is, at least in theory, beholden to the people, not to the overclass. The issue of which form of economic control is less dangerous to society is resolved in one’s mind in regards to whether one has faith in the unfettered rule of the capitalist class or in the rule of government, a slightly limited version of the same.

In a directed economy, said Hayek, one would see the unfortunate results of the concentration of power into the hands of the state. “Since the authority would have the power to elude efforts to elude its guidance, it would control what we consume almost as effectively as if it directly told us how to spend our income”, according to Hayek, and this infringement on freedom is the worst possible effect of such an oppressive political system (Hayek, p. 128). But the consequences of unimpeded capitalism lead to the same horror show seen in the hand-wringing of The Road to Serfdom over socialism. Capitalism, left to its own devices, as Hayek would prefer, naturally tends towards monopoly, as larger firms in the market make their presence felt in such a way as to undercut and buy out the smaller, leading to monopoly, which in turn leads to the same effects as governmental control, but without any societal benefit. If one firm out of five in the market provides your preferred product, there is likely nowhere else that can offer it to you in such a way as to be economically expedient. Thus, our consumption is controlled as well as if we were told what to consume by a central authority of the federal administrative type- but the culprit is not socialism but capitalism.

Friedrich Von Hayek tries to portray socialism and the concept of the planned economy as a nightmare of epic proportions that will lead down the path to totalitarian dictatorship, but his arguments have no merit when held under scrutiny. The comparison of political dictatorship with that of a dictatorship of economy is a fallacy, the one having very real and negative effects on the populace, the other not always being the guarantor of such a result. Hayek’s understanding of the economic man is obfuscated by his elitism and inability to understand the life of the poor. Hayek’s hand wringing hyperbole about the controlled economy and its dire consequences for humanity falls a bit flat in light of the fact that unfettered capitalism has in fact produced the worst of these imagined results. Hayek can scream and twist the truth all he wants- his argument is weak.