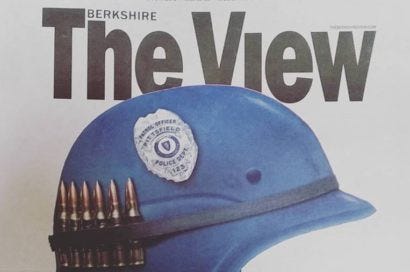

Berkshire County SWAT & No-Knock Warrant Service

In January of 2016, I was approached by an anonymous source. He said he had filed a Freedom of Information Act request with the Pittsfield, MA, Police Department for after-action reports and documentation relating to the operations of the Berkshire County Special Response Team, or SWAT.

The source passed the information along to me in February. My reporting appears in The Berkshire View for May 2016. What follows is a brief overview of that article.

After-Action Report: December 10, 2013

On December 10, 2013, the BCSRT executed a “No-Knock” Search Warrant operation at an apartment on Hamlin Street in Pittsfield. The situation was familiar. The suspect had multiple violent criminal charges from over the years. The suspect was believed to be armed with a deadly weapon.The BCSRT approached the domicile in armored vehicles and mounted what appears to have been a successful mission. It’s impossible to know. The second page of the report is completely redacted.Pittsfield Police Chief Michael Wynn told The View that the redacted portion of the document contained “deployment specific information that was not disclosable due to the description of specific tactics.”What we do know, however, is that by the time is was all over, the police had detained a number of people:“Individuals not secured with handcuffs were allowed, one or two at a time (depending on age), to use the bathroom located at the middle of the apartment.”

Children present were scared and confused by the raid. Team members attempted to calm them:

“Additionally, BCSRT members in close proximity to the young children cleared [their] headgear and engaged the children in an effort to reduce anxiety.”

The anxiety may have been a result of the timing of the raid; the BCSRT left the apartment at 5:50 AM.

[T]he Berkshire County Special Response Team (BCSRT) is the county’s SWAT. It is frequently used for “no-knock” search warrants in the cities of Pittsfield and North Adams and their surroundings.

These “no-knock” warrants are served by SWAT teams, bursting into the homes and apartments of suspects in a paramilitary “raid” fashion.

A heavily redacted after-action report from 2013 describes the beginning and end of one of these raids. Based on what I discovered looking at other reports, we can fill in the blanks.

The BCSRT breaches the door with a battering ram.

The team enters the home and does a first floor sweep, securing any adults and corralling everyone, children included, into one room before checking the second floor.

The same actions take place upstairs as downstairs. The team then does a second sweep of the area, secures the scene, and turns over operational control to on-scene officers.

[A]fter reviewing the internal documents, The View found that warrant service has become the main duty for the BCSRT over the past four years.

In 2012, the BCSRT conducted 14 operations. Of these 14 operations, 7 were warrant-related. The remaining 7 were for barricaded suspects, crowd control, and monitoring gang activity.

A year later, in 2013, the BCSRT conducted 9 operations. 6 were warrant-related. In 2014, when the team again conducted a total of 9 operations, 7 were warrant-related.

By 2015, the team was only being used for warrants. Of the 8 operations included for that year in after-action reports, all 8 were warrant service. Not once in 2015 was the team deployed for crowd control, hostage situations, monitoring gang activity, or any of the myriad other possibilities for deployment in the BCSRT charter.

This push towards the militarization of local law enforcement is a cause for concern.

[K]ade Crockford, the Director of the Technology for Liberty Program for the Massachusetts American Civil Liberties Union, was interviewed for the piece. Crockford gave some background to SWAT teams in general and their use in the drug war in particular.

SWAT teams originated in 1960s Los Angeles. They were created in response to racially motivated violence surrounding the civil rights movements.

“It’s a pretty politically charged history when you consider their origins in racial strife,” said Crockford.

The no-knock warrants, as discussed above, rest on the police’s determination of who is a “high-risk” target, or a “special threat.” This creates the potential for a large amount of wiggle room, Crockford said, wiggle room that can be manipulated by the inherent prejudices or emotional reactions of the commanding officers in the absence of clearly defined written policies.

Crockford also warned about the potential for future abuse of the warrant service and police militarization in general.

“These activities are driving a culture of militarization in police departments that should concern all Americans,” Crockford explained. “Communities of color suffer the most from these drug war raids, but the harm from increasingly militarized warrant service won’t stop at people of color or even with the war on drugs.You might think ‘those people’ are less than or somehow deserving of this horrific treatment, but that’s not only unethical; it’s foolish. Someday you may very well find yourself targeted.”

The full report on the BCSRT, including funding details, more after-action reports, and an in depth look at warrant service, can be found on The Berkshire View’s website.