Arguments of the Anti-Federalists in the Debate on the Constitution

The Anti-Federalists based arguments against the Constitution on a healthy mistrust of state power. This mistrust manifested itself in three distinct ways: a fear of imperium in imperio, or the issue of government within government; the fear of consolidation of power and the supremacy of a central government in such territory; and the fear of human nature itself, which the Anti-Federalists believed would inevitably become corrupt with desire for greater power. These concerns illustrate some of the broader meanings of the Constitution at the time of its conception. In Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution, Jack Rakove delves into these and other discussions of the original Constitution, the Bill of Rights, and the motivations of the Framers, particularly James Madison. Rakove details the genesis of the Constitution through his discussion of the creation of the document and the personalities who were integral to its creation. Rakove also provides an overview of the contents of the Constitution and the historical framework that surrounded it. The Anti-Federalist concerns about the abuses of presidential power, consolidation of state power, and the problems of imperium in imperio, or a government within a government, permeated the debates and drafting of the Constitution.

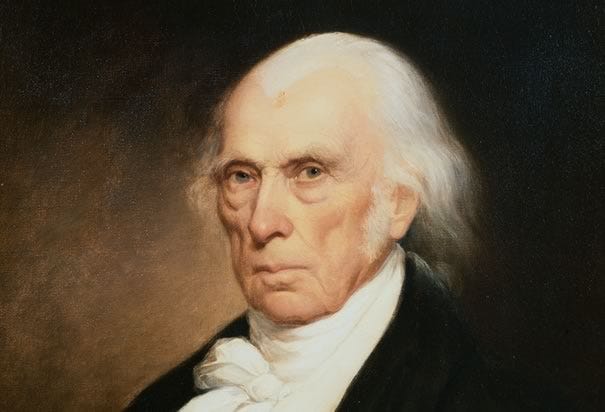

Rakove illuminates in Original Meanings the ideological, philosophical and historical background to the making of the Constitution and its implications for how we can understand the earliest draft of the document today. Using James Madison as the focal point of the book, Rakove explains the deliberations, differences and dissension that occurred in the creation of the Constitution and its background in post-revolutionary politics. Madison, according to Rakove, was the central figure in the drafting and ratification of the Constitution, such that without his influence, the document itself, and our broader, modern interpretation of government, would be incomplete. Within the book, Madison is used as an interpretative tool, one through which we can see the evolution of the Constitution and the arguments in favor and opposed to it. Madison and the framers explicate and clarify these debates, and, further, delineate the reasoning between those who took the federal, more consolidated, statist point of view (the Federalists) and their opponents. Rakove argues that the original intent and reasoning behind the Constitution are highly interpretive and that the current trend of modern historians placing a mythologized libertarian motivation on the part of the Founders ignores the Constitution’s place in history and the personalities and ideas that surrounded its genesis.

The Anti-Federalists had major concerns with the concept of imperium in imerio as applied to the autonomy of state governments and the supremacy of the federal government. The Anti-Federalists posited that the federal state was the perfect example of the imperio, a form of governmental structure that emphasized a strong executive and centralized hub for the government. Federalists contended that the outright coercion necessary for the federal government to exert its will on the states was unnecessary because a strong and total central government could exercise that same coercion by the threat of its legal, financial and military supremacy. The supremacy of the federal government held that those issues resolved by the supreme state would do so at the expense of the sovereignty of the lesser states. The decisions of the federal judiciary would have precedence over the local courts, upon whom enforcement of those laws would fall. Therefore, the lesser states within the federal state had less autonomy and power than their “big brother” or federal overlord. For the Anti-Federalists, this lack of autonomy was a potential evil that needed stopping. To placate these fears and complaints, the framers of the Constitution urged both state by state ratification of the Constitution and the direct election of the House of Representatives. The supremacy clause, which held that the Anti-Federalist fear of an imperio that could swallow the imperium was, in fact, a more benign piece of writing than the Anti-Federalists believed — it placed the responsibility of enforcement of national acts upon the states. Despite the fact these statutes governed them, the states did exercise an amount of autonomy through their abilities of enforcement.

The Anti-Federalists also were incredibly wary of the threat posed to the autonomy of the states of the fledgling nation of the United States by the consolidation of power by the federal government. Reservation within the Constitution of such power of the executive state presented the Anti-Federalist and the Federalist with differing arguments for and against the necessity of the federal Constitution that would define and provide such power. Consolidation was an issue that was dear to the Federalists, given that this gathering of powers was the net result and aim of the Constitution and the federal government that they envisioned. Conversely, the very issues that made consolidation appealing to the Federalists supplied to the Anti-Federalists a cogent argument against what they saw as encroaching state power. The sovereignty of the states within the Union was on the one hand jealously protected by the Anti-Federalists and on the other assured by such Federalist thinkers and proponents as Alexander Hamilton. However, the Federalists offered the caveat that such sovereignty had a cost, and this was the right of protection by the central government which could only have the effect that some of the sovereignty of the individual states would be restricted. With James Madison holding that the states themselves, over time, would become similar through the greater national identity that a cohesive union would provide, the Anti-Federalists feared that this consolidation of territory would by its nature lead to a stronger and more oppressive federal government. The loss of individuality and independence of the states through the strengthening of the central government were thus major issues for both sides.

The Anti-Federalist complaints about the office of the presidency and the workings of the Senate owed much to their uneasiness about the corruptibility of power on those within the government. The Anti-federalists believed that the simple fact of existence of such a power as the executive branch of government would inevitably be corrupted by interests that were opposed to the interests of the American people, be they foreign or domestic. The idea of term limits, though ultimately not adopted for the executive, was introduced to stop the temptation of unending and infinite power for presidents. The thought was that by making the time in office restricted, the risks to those men who would assume the presidency- that they could stand to lose their wealth or influence in trying to gain the power and prestige that the office could provide- would prove great enough that corruption and hunger for power would be tempered. This took from the view of the British aristocratic system that the men who held property and wealth had a vital interest in the viability and stability of the state, the difference being in the United States that there was no natural aristocracy and thus the interest in preserving and maintaining the governmental structure must be in some ways forced upon those who sought higher office. Thus the Anti-Federalists believed that the presidency should be checked so that the danger of an institutional monarchy, or, more frighteningly, a single president becoming a despot, would not come to pass because, so the line of reasoning went, the level of risk involved in grabbing for power would lessen with the constant strengthening of power by a perpetual executive. Similarly, the Anti-Federalists felt that the Senate, with a more aristocratic and less popular makeup of members, could exercise undue influence on the presidency. The Senate as created was elected not by the people of the state but by their elected state representatives, and was therefore made up of a group of men with less to do with the direct interests of the people of the state and more to do with the natural interests of the wealthy and powerful. Collusion between the Senate and the presidency was, for the Anti-Federalists, the perfect example of the corruption of power by the weakness of human nature.

The Anti-Federalist arguments against the entrenchment of state power and the centralization of control over the states by the union were a necessary part of the process of conception and ratification of the Constitution. Without the Anti-Federalist arguments in favor of more independent states and a less all-powerful federal government, the Constitution would have had a far stronger bent towards a powerful centralized state, and the state’s rights issue and term limits for the House of Representatives would likely not have been included in the document. In the broader scope of Rakove’s Original Meanings, one can see the impact of the Anti-Federalists. They were outspoken and disruptive and engaged in a dialogue with their Federalist counterparts that shaped the debate of the day. Rakove does them a good service in his book, placing their arguments and points in the context of his work and the historical and sociological setting that it is presented in. Rakove’s discussion of the topic of the Anti-Federalists within Original Meanings is detailed and clear, and shows the attention to detail and the interpretation of research that his book displays throughout. The historical material pertaining to the matter is thoroughly explicated and put into the broader framework of the making of the Constitution. Original Meanings has an important place in the historical record and interpretation of the early period of American democracy, elucidating as it does the historical, philosophical and personal history of the Constitution.